John Ebenezer Marks was the kind of man you might love or you might hate, but you couldn't possibly ignore. Even King Mindon, in his golden city of Mandalay, discovered that. But at the time this story opens, Marks was an energetic young schoolmaster in Hackney, who had never heard of King Mindon or his golden city. He had, however, learnt to win the love of his boys, and that was the secret of the success which followed him across half the world.

He had learnt his A.B.C. in an East End school, and stayed on to teach the youngsters, preferring the blackboard to an office stool. He tried out his steps, and found his feet, in three Midland schools, then returned to measure his strength against the "Hackney Bulldogs," as the boys of the Hackney Free School were called. They were a tough crowd, [1/2] but he was tougher, and it was neither failure nor cowardice that led him to throw up the job and walk one winter's afternoon into the office of S.P.G. to offer himself for service abroad.

"Where do you wish to go?" asked the Secretary.

"Wherever the needs of the Society are greatest," replied Marks.

"What kind of work do you want to do?"

"Chiefly educational," was Marks' reply.

"Will you go to Moulmein?" came the request.

"With pleasure," said Marks.

"Where is it?"

"In Burma," said the Secretary.

The schoolmaster's professional pride shrank from admitting that he had not the faintest idea where Burma was, and he left the office to pursue his enquiries in secret.

The upshot was that in the middle of May, 1860, Marks found himself, at the age of twenty-eight, on the shores of Burma, after five months' tossing in a cargo boat of 235 tons. No wonder he felt himself in Paradise as he stretched his legs in a coconut grove and knelt down to give thanks for his safe arrival. The lines, truly, seemed to have fallen to him in pleasant places, and the sudden appearance of six jolly. boys, who quenched his thirst with the juice of fresh-cut coconuts, gave him a happy impression of the "bloodthirsty Burmese" against whom he had been warned by kind friends in England.

Three days later, he reached the unknown Moulmein, [2/3] and found it to be a beautiful town on the banks of the Salween River, set against a backcloth of wooded hills, where European houses hob-nobbed with Buddhist monasteries, telling of the new invasion of East by West. In an up-to-date cab, drawn by a Burmese pony, he drove past the wharves, where elephants shifted great baulks of timber with almost human skill, and came through the town to the S.P.G. Mission House, where a tiny school was already in being. There he set himself enthusiastically to the task of learning the language, with boys instead of books for teachers, and laughter instead of yawns to help the work along. [Priests of our Church went to Burma first as Army Chaplains to minister to our own soldiers. One of them wished to start mission work among the natives, and a small school was opened at Moulmein, and a missionary schoolmaster sent out by the S.P.G. in 1859. Dr. Marks was the second schoolmaster to be sent to the country by S.P.G.]

So the adventure began, which was to last for forty years, and bring Marks into touch with one of the strangest and most picturesque kingdoms of the world.

Burma at that time was divided into two: Lower Burma, which was British, and Upper Burma, where King Mindon, almost the last and quite the best representative of a Burmese dynasty, still held sway. [Owing to difficulties on the Indian frontier, the British were forced into war with Burma in 1824 and 1852, as a result of which Lower Burma became British. Upper Burma remained independent until a third war in 1886.] For the first few years Marks lived only in Lower Burma, where the picturesque inconsequence of the natives was being gradually modified by the matter-of-fact British Government. But whenever he [3/4] steamed up the Irrawaddy River to the Northern frontier, he gazed longingly over the border and wondered how soon fortune would let him set foot in that land which, from all accounts, was more like an "Arabian Night's Entertainment" than a kingdom of the modern world.

King Mindon lived in Mandalay, the golden city enclosed four-square in rose-red walls and girdled with a lily-strewn moat. Below the walls dreamed golden barges with dragon-shaped prows. Above them, over snow-white bridges, rose golden spires and white pagodas, painted palaces and shining roofs of many tiers. In the centre of all towered a seven-storeyed spire, or pyathat, which marked the Lion Throne on which King Mindon sat in his palace, to receive the homage of the world. Woe to the man who failed to bow his head before this symbol of majesty, or lower his eyes as he stepped, shoeless, into the presence of the Great King, Lord of the Rising Sun and Ruler of Life and Death! (But to help the memory, Mindon had thoughtfully provided an entrance gate only shoulder high, and a crop of sharp nails in the palace floor.)

So dazzling was the splendour that men caught their breath in wonder, and never noticed that the "silver" gleaming so bravely among the gilded spires was only corrugated iron, and the dazzling walls around the Lion Throne were only bits of glass stuck [4/5] on with glue. They forgot gruesome tales of human sacrifices buried beneath the walls, and of officials who "died of grief" in the royal prisons when they displeased the King. And when the King rode out in state on the Lord White Elephant, to plough a "gracious furrow" with a golden plough, they forgot the pinched faces of the country folk, whose very living was squeezed from them to pay for all this luxury.

It was a land where splendour walked hand in hand with poverty, culture with barbarity, beauty with absurdity. And for the young schoolmaster, fresh from England, it became the Mecca of his ambition.

But there was no time to be wasted in daydreams. For the next eight years Marks was hard at it, founding schools here, there and everywhere, and, as often as not, taking chaplain's duty as well. In eighteen months, his Moulmein school had trebled its numbers, and even the Buddhist monks, who from time immemorial had been the schoolmasters of Burma, brought him their best pupils. "Here, Teacher," they would say. "You take this boy. I have taught him all I can."

His next venture was in Rangoon, the capital of Lower Burma. A school was wanted, but there was no money, so he preached a "begging" sermon in a tin church as hot as an oven, and soon had a well-filled subscription list. He brought ten of his boys from Moulmein and opened school in a cramped little house [5/6] called "The Cottage." The boys said it was haunted, and raced shrieking into the garden in the middle of the night. The "ghost" turned out to be the master's dog, tapping his tail on the floor as he scratched for fleas. But boys brought up in the fear of evil spirits were not easily reassured, and there were many ups and downs before the school finally settled happily into new buildings, under the name of St. John's College.

As soon as the school was able to take care of itself, off went Marks in a steamer up the Irrawaddy River to found village schools, with half a dozen boys and a collection of desks and maps to help him.

Nothing daunted him. In one place they scrubbed out a house and built a bridge over a ditch to the door, only to find their work destroyed by floods next morning. In another, Marks had to drop his dignity and live Burmese style for a fortnight, eating with his fingers and sleeping on the floor. One school was so thinly tiled that they were nearly scorched under the April sun. But they were welcomed everywhere, and even the monks raised no objection to the Christian teaching. "It is like curry," they said. "All need the rice of secular education. We give the curry of Buddhism, you of Christianity. Let them choose which they prefer." So from the lips of Buddhist and Christian boys went up the daily prayer, "Give us this day our daily rice."

Everywhere, the boys proved to be jolly, affectionate [6/7] fellows, but unreliable, and the great task was to get them to work steadily. Sometimes, when the fit was on them, they would take their books to bed and study as long as the light allowed (lamps were taboo, for fear of fire). At other times, an extra half hour's practice on the rifle range would bring them to Marks with a hopeful request to be excused the rest of the day's work. One boy disappeared from school at the time of an important examination. He returned smiling, and after a caning, recovered his smile to explain disarmingly, "Please, Sir, I got married. May I bring my wife to see you?" Some boys used to fly into tempers, bang their heads against the wall and lie on the floor screaming, and in their case a touch of the cane worked wonders.

In 1863 Marks was ordained deacon in Calcutta, and later became a priest. After a furlough in England, he brought back a trained schoolmistress, Miss Cooke, to start work among the Burmese girls, and also opened an Orphanage for Anglo-Indian children, whose fathers had vanished, leaving them to be brought up as Buddhists in the homes of their Burmese mothers.

Several times Marks was seriously ill, and it was sheer determination which brought him back to his work in face of doctors' vetoes. Once his nurse, an Indian man, a convict from a prison hospital, attacked him as he lay helpless in bed, and would have strangled him had not the servants heard his cries. Money [7/8 ] worries, too, pressed upon him, for he was deplorably happy-go-lucky in the management of his affairs. At one time, he was rescued from desperation by the sudden remembrance of a large sum of money, which he had handed for safety to a bank manager and promptly forgotten.

But through everything his sturdy faith upheld him, and he never ceased to have a fund of entertaining, if rather egotistic, conversation with which to amuse his friends.

At last, in 1868, came the longed-for summons. A black palm-leaf letter, signed with a peacock, brought an invitation from King Mindon to found a school in Mandalay.

"Don't go," said the authorities, afraid of political complications. Even the Indian Viceroy tried to dissuade him, and at last shrugged his shoulders and said, "You go on your own responsibility. If you are imprisoned or killed, it's no use crying to us for help." Marks replied with a twinkle, "Under those circumstances I will be perfectly quiet!"

So he got his way, and with his six best boys set off upstream to the golden city of Mandalay. A dream come true at last!

As soon as they crossed the border into Upper Burma they noticed a change. Houses were smaller, people were poorer, life was more primitive, less orderly. The boys had their shoes stolen as they paid their respects to the governor of the first river station [8/9] over the frontier. They saw petroleum drawn from a shaft by the simple expedient of a man racing down hill with one end of a rope, while the other raised the bucket.

Once in the Golden City, they had leisure to drink in its splendours before King Mindon sent for them to the Court. Then they climbed into bullock carts, over the animals' backs and bumped away through the streets and across the shining moat, till they felt every bone in their bodies was out of place. Through the low red postern they went on foot, bowing their heads as they entered the Palace enclosure, and turned aside to see the Lord White Elephant in his painted house. (He was not white at all, really, but had the twenty toes and red-rimmed eyes of official "whiteness" and his skin turned red when it was wet.) He looked a surly brute, and tossed a bundle of hay at the visitors before they climbed the steps to the Hall of Audience.

There in a painted room, with gilded pillars and sparkling walls, they took their place among a crowd of visitors, tucking their feet out of sight as they sat on the floor, their shoes left humbly at the foot of the steps outside. A bell tinkled, a curtain parted, the whole crowd grovelled on their stomachs (except Marks) and the great King Mindon entered.

A dignified, portly gentleman, with a pleasant face, gorgeous robes and a nasty habit of chewing betel-nut and spitting into a gold spittoon. When he [9/10] rode through the streets, all the citizens had to retire behind a wooden palisade, and woe betide the peeping Tom who failed to prostrate himself. In a land where rank was measured by umbrellas, only the King and the Lord White Elephant were allowed white ones, and the King had nine. To address the King in everyday talk, instead of the flowery Court language, was a criminal offence, and it was a nasty moment for an Englishman who once ignorantly replied to his Majesty with the Burmese equivalent of "Right-o, old bean!"

Mindon was an enlightened monarch. He enjoyed showing condescension to the representatives of other little countries, such as France and Britain. He sent Queen Victoria a present of a gold spittoon, like his own, but as she had never acquired the betel-chewing habit, she mistook it for a flower bowl. He also liked to patronise religion and learning, and Marks was the third Christian missionary invited to his Court, the others belonging to different denominations.

As Marks gazed, not in the least over-awed, at this magnificent gentleman, the King whipped up a pair of field glasses and stared at his visitors, finishing up with the Englishman. A herald sang out his name and business and the King opened a friendly conversation, assuring Marks that he was ready to grant any requests he might make.

Seizing his opportunity, Marks asked permission to preach the Gospel, to build a church and school, [10/11] and begged for a piece of land for an English cemetery. The King was as good as his word, and promised to build church and school at his own expense, but, oh! what weary delays there were before the work was done.

At last the Royal School was opened, and nine of Mindon's sons attended it. They arrived on elephants, with forty followers apiece and a fine paraphernalia of gold umbrellas and spittoons. When they entered the schoolroom, all the other boys flopped politely on to the floor, and Marks had a regular game of ninepins with them, till the princes came to the rescue and told the boys to treat them as ordinary schoolfellows. Other boys from the Court came too, "sons of tea" as they were called because they handed tea to the King. Many of them were grown-up, but docile enough as pupils. Once Marks gave a caning to one of them for bullying a small boy, and the fellow sheepishly looked up and said, "Please, sir, he's my son."

The royal pupils had a special garden-house built for them, where they could spend the mid-day interval, and they were allowed a few minutes off every hour to smoke a cheroot.

Marks had many an interesting interview with the King, and would not let that gentleman have things all his own way. Once Mindon owed him 500 rupees for school fees and only sent him 200, whereupon Marks promptly returned it. The enraged monarch said that if his ministers had done such a thing, they [11/12] would have been dragged from the Palace by the hair of their heads. "I am bald," said Marks, "so the punishment would be impossible in my case." The King's good nature triumphed and he took the joke. He asked Marks once why he had never married, and on receiving the answer that no lady had asked him, offered one of his own daughters (he had about sixty to choose from and nearly as many sons!). He used to say that he loved Marks as his own son, and allowed him the great honour of having a triple roof to his house.

But in the end he withdrew his favour because the missionary refused to take ship for England to try to persuade Queen Victoria to give him back Rangoon. Politics were outside Marks' field, but the King had no further use for him when he discovered that.

So Marks had to sail sadly back to Rangoon, his dream of converting Mandalay pricked like a bubble. As he stood on the steamer's deck, gazing at the retreating spires, he said he would never return till the British flag floated over them.

His prophecy was true. In 1878 Mindon died and his son, Thibaw, could not support the tottering throne. Urged on by his unscrupulous wife, Supayalat (Queen Soup-plate, the English tommies called her), he began by murdering all his blood relations to make his crown secure, and ended by allowing the British to march into his capital and take from him the kingdom he was utterly unfit to rule.

[13] So Marks went back to Mandalay, by the first train on the new English line, and preached a sermon beneath the British flag in the famous Hall of Audience, now a garrison chapel.

The splendid Court of Mandalay has vanished from this world, and so has Dr. Marks. But his name lives on, a household word in Burma, and his traditions of sound learning and true doctrine live, too, in the schools which he founded. "His works do follow him."

CHAPTER II. THE LAND OF LAUGHTER. Eight o'clock on a November night last year. Above, a full moon shining brightly down. Below, a crowd of people, a blaring band, smoking torches, reeking lamps, and an air of delighted expectancy. For this is the first night of the Buddhist Festival of Tawadeintha, and the play is about to begin.

The stage stands fifty feet high, crowned with a seven-roofed pyathat. It represents Tawadeintha, the second heaven, and the play will show how the Lord Buddha mounted from earth to heaven to preach to his mother in her heavenly home. A sloping stairway marks the path of his ascent, and the whole is gay with paint and decorations, and tapering miniature spires.

A cry goes up! The procession has started! A troupe of actors in their gayest clothes appear, and a seated image of the Lord Buddha is placed at the foot of the stair in a little carriage. To the tune of sacred songs, he bumps his way to heaven, followed by kings with white umbrellas, spirits in rainbow hues, and winged creatures from the upper sky. Once in [14/15] heaven, they gather round the sacred image, while a voice declaims the Buddha's sermon.

At this point the audience are apt to take out their cheroots and gossip, not out of disrespect for the Buddha's words, but because they cannot understand the sacred language. But they will all turn up again to-morrow night to see the Lord Buddha return to earth.

Meantime, there are lots of other amusements for them. All through the three days of the feast, bands are playing and gay processions throng the streets. "Christmas trees" hung with presents, pasteboard towers representing the heaven of Tawadeintha, and a hundred other offerings are taken with song and dancing to the monasteries. In every street, there is singing and acting all night long, and the excitement reaches fever-heat when an illuminated paper dragon, a hundred feet long, plunges his way through the streets till his candles sputter and die.

Oh, Burma is the land for laughter and jollity, for gay feastings and light-hearted revelry! Where else in the world would respectable, middle-aged citizens go through the streets splashing one another with water? But in Burma it is a disgrace to have dry clothes at the New Year Feast. Where else would soldiers on parade stick their tin hats on their bayonets, and drop out of rank to light their long cheroots? King Mindon's soldiers did it (and off parade they stuffed spare tunics in the cannon's mouth [15/16 ] and carried their uniform over their arm for greater comfort). Where else would people see their homes burnt to ashes in the daytime, and laugh all night among the ruins at actors on a rigged-up stage?

Perhaps they are right; for as we know--

"A merry heart goes all the way,

Your sad tires in a mile--a."And, being Buddhists, the Burmese know they have a long, long way to go, through endless existences, before they reach the happy state of Nirvana. [Nirvana is the Buddhist heaven. It is explained more fully further on in this chapter.] So they step out light-heartedly, and turn all life into a joke.

The soil is kind, so why work hard? This life is short, so why seek wealth? The future may hold sorrow, so why not laugh now? And laugh they do, with all their might, except those who feel the weight of those endless future lives pressing too heavily on them. They put on the yellow robe, retire into a monastery and embrace the Eightfold Path as a short cut to Nirvana.

The Burman lives his life in a plain little house of wood or bamboo, standing on posts and roofed with thatch or wood. Before the British came, he was not allowed to use brick or to gild his house, and even now he is more ready to spend his money on building a pagoda or monastery than an elaborate house for himself. He is content with floors of wood or split [16/17] bamboo, with mats for beds, earthen pots for saucepans and lacquer trays off which to eat his rice. Two meals a day, of rice and curry, are all he asks, with betel-nut to chew and green cheroots to smoke. A bath by the well, a little work in the paddy-field, a gossip with the neighbours, a chance to acquire enough "merit" to make his next life pleasant--what more can man need in this world?

Even the women in Burma can laugh their way along. It is true that, according to the Lord Buddha, they have less soul than a dog. But they are free; free to come and go, free to choose their mate, free to make and to spend their own money by independent trading. They work hard, but that is the lot of women most of the world over, and the only hardship they would gladly be spared is the "roasting" inflicted after childbirth. For seven days the unfortunate mother is kept before a roaring fire, loaded with blankets, pressed by hot bricks, with paint applied outwardly and medicines inwardly. She looks ten years older after it, but so strong is the force of tradition, that she feels half a criminal if she accepts the gentler treatment of the West.

Both men and women go gaily dressed. The men bind a paso round their waist, a long strip of cloth some four feet wide, which falls like a skirt to their ankles, one end hanging gracefully from the waist in front. The paso is always brightly striped and coloured, and a white cotton jacket and silk [17/18] handkerchief bound round the head complete the outfit. The women's skirt, or tamein, is closer-fitting, but equally gay in colour, and they too wear a white cotton jacket. Their silk or muslin scarf is worn over the shoulders, and bright-coloured flowers adorn their hair.

Everyone wears long hair in Burma (or used to, till the ugly Western fashions crept in), and they take great pride in their black tresses, neatly coiled on the head. Hair-washing is quite a ceremonial business, as an English commissioner discovered, when he awoke to find his fence stolen in the night to enclose a piece of river for a prince to wash his hair in.

In King Mindon's time, there were many pitfalls for the unwary. Only the highest in the land might use silk for their pasos and tameins, and if ever they dared to use the royal peacock in a design, they would not have long to rue it in this world. Umbrellas, too, were risky luxuries, for not only must the colour be right (white for the King, gold for a prince, pink for a Court official, plain palm-leaf for a commoner), but the King delighted to change the length of the handle year by year, and to be out of fashion was not merely discourteous but criminal. As for Queen Soup-plate, the little vixen would almost scratch the eyes out of a lady-in-waiting who dared to appear in a tamein the same colour as her own, or to ape the royal style of hair-dressing.

Life is simpler now. People can build their houses as they like, measure their materials by their purse [18/19] and carry a white umbrella all day long if it amuses them.

I confess to a sneaking preference for the queer old days, when Maung Tha Byaw, a famous singer, was granted the honour of a gold umbrella, and stretched a "royal fence" across the front of his stage, with the gold umbrella at one end and a banana tree at the other. He was "killed" several times at Court, for the crime of singing a new song in the presence of the King--he made up the words as he went along, so never remembered the old ones--but he always sang so sweetly to his executioners that they found some other body for burial, and he was ready to sing again next time the King spoke regretfully about him.

Naming children is no haphazard business in Burma, and can't be settled by the easy method of referring to the cinema star then in the ascendant. It depends entirely on the day of the week on which the child is born. Every day has certain letters of the alphabet assigned to it, and the name must begin with one of these. Monday's child may not be fair of face, but she can be Miss Lovable, Ma Rhin, because Kh is one of Monday's letters. And when she goes in later life to worship at a pagoda, she may burn a candle shaped like a tiger, because the tiger is Monday's animal.

This has the great advantage of allowing people to forget their age if they want to, without forgetting their birthday. But even Dr. Marks found it impossible [19/20] to honour King Mindon's birthday with a school holiday when he found it happened every Tuesday!

Children in Burma have a delightful time. They run about half naked, splashing in and out of the streams, and playing queer games of skittles, football (with a wicker ball) and boxing (with hands and feet). Before they grow up, the boys are tattooed from waist to knees with intricate patterns of animals and symbolic signs, and the girls have their ears pierced with silver needles, so that they can wear thick plugs of gold or jewel or coloured glass in them. In the old days, it was a sure sign of cowardice to seek to avoid these painful ceremonies, but nowadays the enlightened moderns feel no compunction about it.

All down the ages, monasteries have been the schools of Burma. There were no fees, no attendance officers and no certificates, but so willingly did the boys flock to school, that Burma became one of the most literate countries in the world. Hardly a boy grew up who had not learnt to read and write, to use numbers and to recite passages from the sacred writings of Buddhism. Even the girls, whom no one troubled to educate officially, usually picked up enough from their brothers to enable them to run their little shops successfully, at home or in the local bazaar.

The monastery school is primitive and noisy. The boys squat on the floor and shout their lessons aloud, using little slates for writing. The only books are [20/21] palm-leaf scriptures, laboriously scratched by professional scribes and preserved with earth-oil. Such treasures are too precious to be put into the hands of careless schoolboys, so the teaching has to be oral. No wonder the monks began to bring their best scholars to Dr. Marks. How could they compete with the new education, with all its helpful paraphernalia of books and maps and blackboards? Since then, more and more parents have begun to send their boys (and girls too) to Mission or Government schools, and it looks as if the monasteries will gradually drop out of the unequal contest.

But as long as Buddhism holds its sway over the mind of Burma, the monasteries will keep their honoured place in the nation's life. For, to the Buddhist, the life of the monk is the only holy life, and only he who has set his foot on the Eightfold Path is truly a man.

For this reason, every Burmese boy at some time or other must don the yellow robe and enter the monastery as a novice. It is the greatest day of his life. Decked in his finest clothes, he goes the round of his friends to bid them a solemn farewell. Then, in his home, before the head of the monastery and a crowd of assembled monks and guests, he throws off his clothes, his long black hair is snipped with a knife, his head is shaved, and after a bath, he prostrates himself before the monks and begs for admission to the sacred order. From the monks' [21/22] hands he receives his yellow robe and begging bowl, and without again raising his eyes to look at his friends, he follows the monks to the monastery, leaving the family to the inevitable feast and merrymaking.

It would indeed be a solemn moment if it meant the final renunciation of the world and all its attractions. But most boys, after sharing the monks' life for a week or a day or one holy season (from July to October), return to their homes and resume their ordinary life. They grow up and marry, smoke and gossip, work a little, play a lot, and take up the happy heritage of their race. Henceforward, their religious activities consist of occasional visits to a pagoda to make offerings and recite texts, occasional efforts to "acquire merit" so that the next life will be at least as pleasant as this one, and whole-hearted participation in all the fun of the religious festivals.

For those who choose to retain the yellow robe, life is a more serious matter. The monk never marries, and he carries a fan wherever he goes lest his eyes be caught by some fair charmer. He eats no food after mid-day, and takes his begging-bowl round the village each morning for the offerings of the faithful. But he inflicts no other torments on his body, and except for teaching the village boys, his only care is to pursue his own path towards Nirvana, with as great or as little zeal as he chooses.

Buddhism is a sad and curiously selfish faith. Life [22/23] is suffering, preached Gautama, its founder. And since life is produced by desire, the only way to end suffering is to end desire. The follower of the Eightfold Path strives to kill all desire in himself, both bad and good, and hopes by that means to reach Nirvana, where suffering ends in the extinction of life.

Gautama said, "There is a God-spirit," but he gave no teaching about Him, and for the ordinary Buddhist there is no God, no prayer, only the sorrowful meditation summed up in the words, "To live is to suffer; all passes; there is no soul." But though they say there is no soul, they believe that all the actions of a man's life are added up and passed on to the next existence, like a sort of profit and loss account. If his life has been bad, the loss outweighs the profit, and he will be born again in one of the four "states of punishment," perhaps as an animal or fish. If his life has been good, his next existence will be spent in one of the "blissful seats" of the spirit-world. But not till he has acquired the full sum of "merit," by constant meditation and the ending of all desire, will he reach his final goal.

Hence arises the curious idea of "gaining merit" which gives even good actions a selfish turn. The villagers run out to feed the monks as they walk in procession through the streets, but they do it less to help the holy men than to acquire merit for themselves. There is great merit in building a new pagoda, [23/24] none in repairing an old one, so Burma is strewn with the wrecks of sacred shrines. A slave is a slave and a leper a leper because of his sins in a former life, so it is useless and unnecessary to pity or help him. "Each man must bear his own burdens; each man must tread his own path."

It is one of the strangest facts about Burma that while the religion of the monks is so sad, the life of the ordinary people is so happy. There is only one explanation of the riddle. Every man who dares to take Buddhism seriously feels himself compelled to become a monk. So the light-heartedness of ordinary folk is either the careless jollity of people to whom religion means very little or the hectic merry-making of those who dare not face its stern realities. To be a good Buddhist is to be a sad man.

So the monk meditates in his monastery, caring nothing for the souls of others; the layman laughs in his home, caring nothing for the sufferings of others; and the pagoda slave sweeps up his courtyard, despised and an outcast, his only hope the acquiring of sufficient merit to make his next life happier.

The pagodas are the glory of Burma. They enshrine not only sacred relics of religion, but all the love of splendour and extravagance which finds no outlet in the common buildings. They are not so much temples as shrines, to which people come to worship privately (if reverence paid to "Buddha, the Law and the Order of Monks" can be called worship). [24/25] They are of every shape and size, and nearly all are covered with gold leaf. In Rangoon, the Shwe Dagon Pagoda rises to a height of over 300 feet, and the upper part is encased in gold plate costing £50,000. Above it stands a sacred umbrella, covered with gold and precious stones, and enshrined within are eight sacred hairs of the Lord Gautama.

In the Arakan Pagoda, Mandalay, sits a bronze image of Buddha, twelve feet high. History tells how it was brought over the hills in 1784 when Arakan was conquered, and legend adds how the great Lord himself came down to earth to fit the pieces together. One small pagoda stands on a boulder at the summit of a 3,000 feet hill, balanced as if a gust of wind might send it crashing to the bottom. Others are perched on precipitous cliffs, or built in fantastic shapes, like dragons or mushrooms.

They all have their yearly feast days, when pilgrims bring their offerings, and all have their legends, strange tales of bloodshed, miracle or piety. And to them on four "duty-days" each month, the pious layman may come to acquire merit by chanting the praises of Buddha and fasting, like the monks., after mid-day.

But after all, "Each man must tread his own path." So there is no one to worry about the man who prefers amusing himself to acquiring merit. It is nobody's loss but his own. Some day a "flag of the King of Death" may appear among his black hairs, [25/26] and he will stop to think. But till then, he will smoke and gossip and laugh, stand all day to see a boat race, sit all night to see a play, gamble his money away to avoid taxes, and send out packets of picked tea to invite his friends to feast. Who will blame him? Certainly none of his fellow countrymen.

"To live is to suffer; all passes," says their religion.

"Eat, drink and be merry, for to-morrow we die," echo the people. And they do it with all their might.

CHAPTER III. FROM BUDDHA TO CHRIST. A sad little boy of six walked behind an old monk through the streets of a village in North-West Burma. He was an orphan, for the King of Death had suddenly robbed him of both father and mother and the old monk had taken pity on him and promised him a home at the monastery.

There the child forgot his sorrow and grew up as a devout follower of the Lord Buddha. Every morning he carried his master's sandals on the daily begging-round, and swept the floor of the monastery. When school began, he took his place among the other boys and shouted aloud the sacred scriptures, or crouched on the floor over his little black slate, afterwards playing skittles with them in the shady patch under the building.

When he was old enough, he donned the yellow robe of the novice and lived no longer as a scholar but as a monk. He slept at night on the floor of the monastery hall, and took his place in the early dawn before the image of Buddha to chant the great Lord's praises.

[28] "Praise be to the Glorious One, the Worshipful, the All-enlightened.

I turn to the Great Lord as my refuge.

I turn to the Great Law as my refuge.

I turn to the Great Monkhood as my refuge."All day long he learnt to meditate on the meaning of life, with the help of the writings of Buddha and the teaching of his old master. U Nyaneinda, "Wisdom is my Master," was the name the monk had given him, and he was true to it.

There came a day when in the sacred writings he found the phrase "There is a God-Spirit." "Who is he?" asked Nyaneinda. But none could give the answer. Then Nyaneinda set out on a great quest. "I will never rest until I find the God-Spirit," he said.

First he learnt all he could from the monks at hand, but they left his soul still hungry. Then he followed his master through Bengal and Ceylon, but in the greatest monasteries of those lands he found no answer. His master died, and Nyaneinda went to Mandalay, but even in the royal monastery of a thousand monks was none to help him. So, like all true seekers, he went into the wilderness, and by ceaseless prayer and fasting sought his answer. It came, but not in the way he thought to find it.

In the town of Pegu he found a Christian church and men told him it was the shrine of the God-Spirit. [28/29] Too shy to enter, he spoke to a priest, who gave him a New Testament in Burmese. "God is a Spirit," he read. And "God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son . . ." Could this be the end of his quest?

Still pondering deeply, he found his way to the Divinity School at Kokine, where men are trained for the Christian ministry. There his search ended. For on December 15th, 1934, Nyaneinda cast off his yellow robe and received the cross of the catechumen. On St. Peter's Day, 1935, he walked joyfully down to the lake for his baptism and emerged with the new name of Peter Shwe Nyan (Golden Wisdom).

There his old life ended and his new one began. He went back to tell his friends, the monks, about his new-found joy, but they spurned him with cries of "Beast! Mad Dog!" and drove him away with curses. Peter Shwe Nyan was not daunted. "St. Peter was a rock," he said. "I will be one of the rocks of the Burmese Church." So he set to work to write the story of his search for God, and a letter to Buddhist monks, and, like St. Paul, he can turn their own scriptures into a weapon of conversion, for he knows them inside out. What the end of it all will be, only God knows. But here is a man to whom He has shown a path from Buddha to Christ, and perhaps one day it may become a well-worn track.

Ever since Dr. Marks opened his schools, Christians have been at work among Burmese Buddhists, [29/30] preaching, teaching and caring for the sick. That their work has had a tremendous effect none can doubt, but it has not been altogether the effect that missionaries hope for. They have stirred the Buddhists not so much to conversion as to imitation.

The Buddhists saw Christians tending the sick and helping the poor; they, too, began to visit prisons and help the weak. They saw the lives of young men raised by the Y.M.C.A.; they formed a Young Men's Buddhist Society. Christians opened schools for girls, so Buddhists began to think them worth educating. Christians taught and prayed in everyday language, so Buddhists began to preach in the vernacular.

No doubt this is excellent, for imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. But, as the saying goes, it doesn't get us much forrarder with the work of conversion, and Buddhism itself is a very hard nut to crack.

For one thing, it is so closely bound up with the ordinary life of the people. A Burman may not take the deep things of his religion very seriously, but many times a year the great festivals offer him the chance of acquiring merit in the jolliest possible way, while the daily procession of monks through the streets is a constant reminder to him. Again, the presence of so many thousands of monks adds enormously to the strength of the Buddhist fortress. None but the tiniest village is without at least one monastery. The monks are not only the teachers of religion, but they [30/31] are held in the highest honour as men engaged in the noblest pursuit there is--meditation. No one treads on their shadows or speaks to them in the common tongue. They are above criticism and above the ordinary law. When they die, they are honoured with a funeral as splendid as a king's.

Then, again, the teaching of Buddhism is in many ways excellent. Who could quarrel with the Five Precepts, which all are supposed to keep?--"Thou shalt not kill. Thou shalt not steal. Thou shalt not commit adultery. Thou shalt not tell lies. Thou shalt not drink intoxicating drink." They sound very much like our own commandments, leaving out those which refer to God.

And that brings us to the crux of the whole matter. There are four great things which Christianity has that Buddhism has not, and we believe that no religion can be complete without them.

The first is belief in God, the God-Spirit for Whom Nyaneinda sought in vain among the Buddhist monasteries. The second is belief in the soul, whose destiny is not extinction in Nirvana, but living union with the Eternal God. The third is joy, for life itself is not evil but good, and the evil of sin can be cured. The fourth is unselfishness. We do good in order to help others, not to acquire merit for ourselves, and God Himself gave us the example.

God, the soul, joy, unselfishness--on these four rest both our excuse for seeking to convert Buddhists [31/32] and our hope of ultimate success. So the work., goes on, however small its apparent effect. With the dauntless foolishness of which St. Paul speaks, the missionaries tilt at the Buddhist fortress, content to leave results to God.

And there are results. Sometimes they are tiny incidents which show the leaven is at work.

A missionary arrived at the house of a Burmese widow one evening to find a candle lighted in front of her husband's photograph and a young girl slowly reading prayers out of a Christian book.

"It is a holy time for us," explained the woman. "My husband died on a Friday evening." It turned out that the girl was a Buddhist from next door, who read the book straight through, regardless of times or seasons, and ignorant of its meaning. That evening she began on page 105 and read Compline, sixteen "occasional" prayers and a service for a Quiet Day. But who can doubt that her stumbling words were acceptable to God, and perhaps may lead her nearer to Him?

Another time a Buddhist gentleman, with a gold watch chain and black boots added to his immaculate Burmese dress, called after a missionary in the street to ask him about a book he wanted. It was called "Bible Gems," and he had seen a copy by chance, but when he sent to bookshops for it they persisted [32/33] in presenting him with a "Bible Gems Birthday Book," which was not at all what he wanted. He dragged the missionary into his office (he was head clerk of an English firm) to show him the offending volume, and out of his desk came also well-thumbed copies of "The Imitation of Christ" and a book on prayer. Remarkable reading for the off-moments of a Buddhist clerk!

Sometimes things happen on a larger scale, as the story of Maung Tha Dun, the Christian hermit, shows.

He began life as a farmer in one of the villages in the Irrawaddy valley. Like all Buddhist boys, he entered a monastery as a novice, and might have worn the yellow robe for life, but the monks were not zealous enough to satisfy his ardent spirit. So he returned to the world, married and settled down to farming. But in his heart he felt the call to a life of stern renunciation, so as soon as he could provide for his wife and children, he left them to become a hermit. They made no attempt to stop him, for in the East the call of religion is honoured and obeyed.

For thirteen years he lived in a forest cave, wearing a rough, brown robe, eating a single meal of fruit and vegetables each day at dawn. His days were filled with prayer to the One Great God Whose call had sounded in his heart. As he came to know Him better, he felt impelled to go into the villages to preach and to denounce the worship of images, the slack lives of [33/34] the monks, and other evils he saw in popular Buddhism.

Then he heard of the Christian faith, which greatly attracted him. But for a long time he would take no decisive step, partly because he was repelled by seeing some Christian missionaries take part in big-game hunting, and to take the life of any creature is, to a Buddhist, sin. The monk even strains his water before drinking, to make sure that no tiny creatures are floating there. At last he met one of our missionaries, and after eager discussions and much pondering, took the great step. He was baptised with the name of "John the Baptist," for his task was surely to be the forerunner of Christ to his fellow Buddhists.

Still in his old, brown dress, still living the same ascetic life, he set out to convert his former followers, and with two companions, an English and a Burmese priest, he toured the villages to win men for Christ. As he preached, he learnt more and more of the truths of his new-found Faith, and his face was suffused with joy at each discovery. They found their congregations in towns and villages, on landing stages and railway platforms, in the bazaar or near the well. Sometimes they were stoned and persecuted; once the hermit was arrested; often the men who sheltered him awoke to find their crops cut down or their house on fire. But they told their tale, and men, women and [34/35] children were shown the Way of Christ and received their baptism in rivers by the wayside.

An old blind woman came to hear them preach. "This morning," she said joyfully, "I came here in darkness. Now it is night, but I see." An old man said, "That's the Faith I've been seeking for twenty years," and he told how he had left Buddhism to seek God, and how men had stoned his house, burnt his crops and cursed him. Now he was happy.

Maung Tha Dun neither sought nor found any reward for his toil, except the happiness of serving his Master and bringing His Light to others. He died in 1918, and surely his life is one of those "grains of wheat" which has fallen into the soil of Burma to bring much fruit to life.

Certainly, Buddhist monks have begun to show more interest in Christianity of late. Last year nine of them appeared side by side at a Christian service. Four of them came to the Mission House in Mandalay to ask questions. The questions stretched out over six interviews lasting four hours each, so somebody must have been interested! Here are two of them: "If all was darkness until God created the light, where did the darkness go when God made the light?" "If you say that God can create, why should He not here and now create a boy?" Could you answer them?

On another occasion a letter was handed in to the Mission House at Mandalay addressed to "His Grace [35/36] the Lord Archbishop of Mandalay." It proved to be a request from a Buddhist monk for a book on Christianity,--in English so that the other monks should not know what it was about. A Burmese priest took the book and found the inquirer sitting in his yellow robe, teaching small boys the English alphabet. The monk had been to an English University and had taken a degree, but never till that week had it occurred to him to wonder what the white man's religion was about.

Of course the best way of winning the interest of Buddhists is by training up Burmese men as Christian priests and teachers. Then, with all their knowledge of Buddhist ways, they can meet and answer them on their own ground better than strangers can ever hope to do. So the centre of all the evangelistic work is the Divinity School at Kokine, where Nyaneinda found the end of his quest.

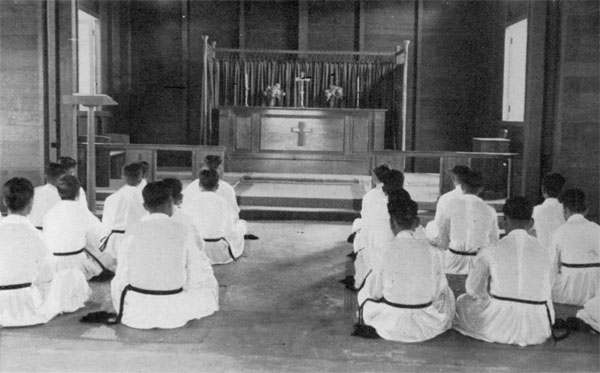

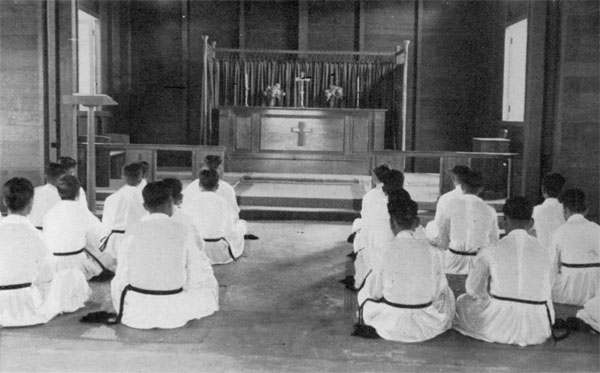

The Divinity School stands in the compound of Holy Cross Church, near Rangoon University. In it men from all the different races that inhabit Burma are trained to be priests. This is how one of the students describes them:

"Though we are different in colours, customs and languages, we are of one blood, one body, one spirit and one faith in Christ's Body which is the Universal Church. We worship in the same Chapel, eat and drink out of the same pots and share the same kinds of work in our College life. Our brotherly affection [36/37] and kindly sympathy towards one another is limitless. We have come to be trained as priests to serve Christ, to sacrifice our lives to the growth of the Church and to devote ourselves to Christ's ministry in Burma."

Their life is simple. For Chapel they wear white cassocks and sit barefoot on bamboo mats. Their lectures are given in English by "men of calm endurance and sympathy" (to quote the same student). They clean the buildings themselves, and often laugh over their meals, which are "neither too good nor too bad." They help to look after the people in several villages which are in Holy Cross parish, an excellent training for their later work. "Oh, how happy and delightful we are," says our student, "when we meet our church people, who receive us with smiling faces, cheerful attitudes and with the best accommodation. We visit their houses individually, encourage them to be firmed in the faith and to be regular in their worship, and pray for them. We eat and drink together."

Delightful we are sure they are! And no better way could be found of sharing in Christ's work in Burma than by helping to pay for the training of one of these men.

Later I will tell you the full story of one of them and then you will understand what it all means.

CHAPTER IV. BEARING ONE ANOTHER'S BURDENS. Take the "hand" of a trout-spotted gekko that haunts old trees; mix in equal parts of sulphur and cock's dung; add the bulb of a white lily and a chilli, roasted; heat slowly, stirring all the time, and add some earth oil before applying.

How would you like to try that ointment as a remedy for whitlow? A Burmese doctor used to prescribe it regularly.

Or if you feel really ill, and can't tell what is the matter, send for the witch-doctor. He is almost certain to say that you are bewitched and tie a rope round your neck to twitch the spirit out. If it does not come out, he will thrash you with bamboo rods, stick pins into you, rub red pepper in your eyes, and the more you shriek the better pleased he is, for it proves that the evil spirit inside you is responding to treatment. You will need a pretty tough constitution to recover from his attentions, but fortunately he only practises in remote jungle villages nowadays.

The trouble in larger places is that there are so many doctors and quacks that the poor patient hasn't [38/39] a chance. He falls ill, gets frightened, and sends for four or five doctors all at once. The first arrives, says his liver is out of order and gives some medicine. The patient is no better ten minutes later, pays the doctor, dismisses him and waits for the next, who puts the trouble down to the blood, prescribes accordingly and again is dismissed when no immediate cure takes place. The third prescribes for the heart, the fourth for the chest, and so on till the patient has swallowed a whole drug shop, and his only hope of a cure is if the supply of doctors or money runs out in time to save him!

It all sounds rather sad and rather laughable, but don't be too scornful of the credulous Burmese till you have had another look at the advertisement pages of our own magazines. What about the pills which cure everything, and the promises to make you taller or slimmer while you sleep? Somebody must believe in them!

In the golden city of Mandalay, overlooking the moat which once enclosed the home of kings, stands a two-storeyed hospital. Upstairs is a cheery ward for women and children; downstairs are three little wards for mothers and their new-born babies, and a dispensary where sixty out-patients are treated day by day. It is the Queen Alexandra Hospital for Women and Children.

Here from all parts of Mandalay and from jungle villages far and wide, patients bring their bodily ills [39/40] to be healed and their poor, untaught minds to be freed from the tyranny of age-long superstitions. Think what it must mean to a mother, who was roasted and almost suffocated for seven days after her first baby's birth, to lie peacefully in a bright little room in the hospital with her second child, with kindly nurses to care for her and two other young mothers in beds near by to gossip to. But often and often they have a terrible struggle with the old women of their village before they are allowed to come, and if there is no one at hand to help them, they may give in from sheer weariness and submit to the old ordeal.

Don't imagine that all Burmese doctors are charlatans, and all their treatments cruel or useless. They have some remarkable herbal remedies which sometimes succeed where European doctors have been baffled, and their use of massage is often excellent. But the fact remains that there is a great deal of unnecessary suffering, as a Mission Hospital soon discovers.

Maung Galay, a sturdy little chap of five, was brought by his mother in a terrible condition. He had trotted to the fire to inspect the dinner while his mother's back was turned, and had fallen headlong into the great black cooking-pot. "Rub ink into the blisters," suggested a helpful neighbour. No wonder Maung Galay's shrieks could be heard from afar, as his mother brought him down the river and in a jolty [40/41] bullock-cart to the hospital. His burns were dressed, the screams stopped and his mother was persuaded to let him stay in the hospital. "He will die if you don't leave him with us," said the doctor. So Maung Galay stayed till his wounds healed, and when his mother went back to her jungle home, she told her neighbours how good and safe the hospital was, and taught them that the old ink remedy must be used no more.

Another time, a little girl was brought. Her ears had been bored, but the holes were not quite big enough, so her mother had stuck bits of dirty wood into them. The wounds had turned septic and spread till the pain sent the poor little thing completely off her head. She, too, was nursed back to health, and for the first time her village learnt that cleanliness is more than a mere fad.

It is not only the patients who take new ideas back to their villages. The nurses, too, are trained for three years in the hospital and then go back to their jungle homes with all their knowledge and desire to help. Some of them marry and settle down, but there is a scheme afoot to send some to work as "district nurses" in the jungle villages. They could do untold good, but of course it would not be fair to send girls to face all the opposition of ignorance and superstition quite alone. They need to be linked up with some hospital or doctor who can back them up and help them.

Sometimes little orphan children are brought to [41/42] the hospital, or babies whose mothers have died, and they sadly need room in which to care for these tinies. Children with rickets, too, appear--pathetic mites whom only long months of care and good food can restore to strength, and there is nowhere for them to live except among the other patients. Perhaps soon they will be able to build new rooms where these little ones can be given a better start in life.

There is another need which, alas, money cannot supply. There is no resident doctor in the place. Two English Sisters are in charge, and a Hindu doctor comes in every day. But all the time they are hoping for an English woman doctor to come and join them. If you know of one who can cure bodies and win souls too, tell her. Burma is waiting.

The work of healing is only one side of a Mission Hospital's task. It is the other, the preaching of the Good News, which makes it different from an ordinary hospital. There is a little chapel, St. Raphael's, in the same compound, where services are held each day, and patients who are too ill to move hear prayers read in the wards. All the nurses are Christian, and the two English Sisters in charge do all they can to make the hospital a real mission centre.

Old Ma Hmun has gone home after a long illness with a genuine interest in Christianity. She talks of the hospital to all her friends and neighbours (who look on her cure as a miracle), and the Sisters are looking forward to holding meetings for inquirers in [42/43] her house. Perhaps some of them may one day ask for baptism.

Every morning the hospital is visited by students from the "Missionary School," which also stands in the same compound. This is quite a new venture, only begun last year.

You have heard how the Divinity School is to be the power-house where men are trained to win Burma for Christ. In Mandalay the "Missionary School" has been started to be a power-house for women. Students go for one year to train as women evangelists. They pray and study, visit and teach, and afterwards go out into the world to be Christ's witnesses. There are not many paid posts for them to take up. The idea is that they shall do their ordinary work as wives and mothers, teachers or nurses, and at the same time become little centres of Christian influence in their homes or schools or hospitals.

At the beginning of this year (1937) there were only nine students, but several others are already asking for admission. At the end of the year, some of them are going straight to the Mission Hospital to train as nurses, so the two kinds of work are closely linked. The cost for the year's training is only about £10, and it would be a real adventure to pay for the training of one of them, for who knows into what far corner of Burma they will land eventually?

Perhaps some of the women may go to join Miss Cam in the Delta. She used to be at the Queen [43/44] Alexandra Hospital, Mandalay, and has now opened a little hospital and four village dispensaries of her own in the South of Burma. Tiny places they are, built near the edge of the river, for most of the patients arrive by boat. You would not ask why if you had ever ridden in a bullock cart when you felt ill.

At Pedaw, all the young mothers come with their babies for advice and treatment--another refuge where they can escape their roasting. Miss Cam lives here, and the two things that make life bearable, amid continual floods and mosquitoes, are the little oratory where they all meet for prayers, and an outsize mosquito net into which she can retreat in the evening. All through the rainy season she has to wear great sea boots as she splashes through swamps and mud, but a duck-board landing stage at the hospital makes life easier both for her and the patients.

At Nyaung Ngu, across the river, all sorts of cases are treated, and a few in-patients settle there on their mats, though there is only one large room and a small one screened off for examinations. To and fro Miss Cam goes in a frail canoe, watching her hospital patients, touring round the villages with a tiny dispensary, and always finding time to teach and pray and encourage too. Think of her sometimes as she sits on the floor of her hospital after sunset, singing "Light at eventide" in Burmese, with a couple of patients, one or two of their friends, the house boy, [44/45] motor-boat boy, and a few storm lanterns to break the jungle darkness.

Down in Rangoon there is another little centre of women's work, where perhaps one of the students may land when her training is done.

Picture two little girls dancing happily in their village home after seeing an open-air play. Hear a city man bargaining with their parents to take them to Rangoon to be trained as dancers. See the two children down in the city, fallen into bad company, caught and held prisoner in an ill-famed house. The elder scribbles a plea for help, ties it round a stone, drops it in the street, and presently an Indian man picks it up and takes it to "the lady who helps girls to go home from dancing-houses." Backed by police, she goes to the house. "If you do not release the children," she says, "we stay here to look after them." The children are released, and as soon as the fear of recapture is over, two happy sisters return to their village home.

This is the work of the Vigilance Society in Rangoon, and many a girl has grateful memories of Miss Niccoll Jones and Miss Cooper, who rescued them in their hour of need and gave them shelter in the Home they have opened.

Up and down the country, in towns and villages, there are Christian schools and churches, little centres of work and witness, from which the 'light of Christ shines, as from a lighthouse, across the dark seas of [45/46] Buddhist Burma. High schools in Burma are not so very different from our own in England, with their games and prefects, houses and speech days; village schools, which are very different, I will tell you about later. But there are two schools I would like to tell you about now, partly because they are quite different from any others, partly because, like the other ventures described in the chapter, they are part of the Church's special charge of caring for Christ's poor little ones whom life has left with a handicap. I mean the Schools for the Blind.

The Mission to the Blind of Burma is a romance of which the first act was played in England, in a home where a little boy went blind. But Willie Jackson, as the little boy was called, romped his way to manhood, heedless of bumps and the anxious care of elders. ["An Ambassador in Bonds" gives the full story of William Jackson's life and work.] He rode his bicycle, climbed roofs, learnt to skate, played practical jokes with all his boyish might, and when, later on, he went to Oxford, the same high-spirited courage carried him through awkward moments, as when he poured milk into the sugar basin or shook his pipe out over a plate of muffins, and through long, laborious hours when papers had to be written in Braille to be read at the Historical Society.

He became a priest and heard through his brother-in-law, the Rev. W. Purser, of a Blind Mission just opened in Burma. The call seemed clear, and in 1917 [46/47] Father Jackson sailed away to his life's work. Alas, it was all too short a life, for he died in 1931 at the early age of 41. But it was lived with so much joy and energy that the blind of Burma will never forget it.

At Kemmendine, he soon had a new school built for his blind boys, with long verandahs where they could run in safety, doors and windows opening one way only, and guiding marks on all the floors. He went long journeys by rail and bullock-cart, and on foot through the jungle, to fetch his pupils and quieten rumours that he sold the boys as bait to fishermen. He invented a Burmese form of Braille to teach his boys, and bought an old mangle at the bazaar to serve as printing-press. He opened a technical school where the boys could learn to be self-supporting, and they made toys and mats, baskets and boxes, and even began to tune pianos and repair boots and shoes. He organised an "after-care" department to help ex-pupils in their unequal struggle through life, and it was his boast that the boys could turn to the Mission for help till the last moment of their lives.

Girls, too, were cared for in a school which finally settled at Moulmein and was visited by Fr. Jackson every month. An Anglo-Indian girl, Rose Davidson, took charge at first, and though several English head mistresses were there at different times, it was Rose's influence which held the school together through all its ups and down, and her loving presence that made it into a home. Like the boys, the girls were taught [47/48] handicrafts which gave them, if not a complete livelihood, at least the happiness and self-respect of useful work.

Father Jackson became known as "Apaygyi," Big Father, and his boys loved him. Day by day, as he offered the Holy Sacrifice, these blind boys served at the altar, and few of them passed through the school without asking for baptism. He taught them to sing, till they were even able to sing for Columbia records and what a feat that was, only those who have been harrowed by the first efforts of Burmese congregational singing can appreciate!). He taught them to act and they produced the first Christian play ever given in Burma. He took them to the Zoo and laughed with the best of them when a leopard shook hands through the bars of its cage. He waltzed round the room to the tune of a gramophone in what he called his "Night Club" for the older boys, and even braved "open nights" when untaught visitors joined them and the dancing became more like a football scrum.

In work and worship, effort and laughter, his life burnt out for Christ. Even the pain of his last, long illness could not quench his joy, and his last words as he lay dying were, "I shall be helping all I can on the other side." Surely the words are fulfilled, for his work goes on and his spirit lives in it still, even as his name lives in the hearts of hundreds of men and women to whom he brought light in their darkness.

CHAPTER V. A PEOPLE WHO CAN BE AFRAID. In a dirty, tumble-down bamboo building away in the jungle, a group of people stand round a winnowing-sieve. On it are four balls of cooked rice, one white, another blackened with charcoal, a third dyed red and the fourth yellow. One by one the people move forward, spit upon the tray and its offerings, and address the spirits thus:--

"Let all pain and sickness depart. Depart, all colds.

Go, eat your black rice, your red rice.

Go, eat your betel and its leaves.

Go, eat with your wife and your children. Go, stay in your house."Then they climb down the rickety ladder, pick up their bundles of possessions from the jungle path and move away to the sound of drums and gongs. The village house, where nine families have lived, is abandoned to the tender mercies of spirits and jungle beasts, and the villagers move off to a new home.

In a small clearing it stands ready, a frail structure on posts, with floors and walls of split bamboo, a roof [49/50] of bamboo tiles, and ample gaps to let air in and smoke out. One of the men steps forward, and from seven adjacent trees plucks upright twigs. With these he enters the building and sweeps the floor of all the rooms, again invoking the spirits.

"Go away, all evil spirits.

Depart, all devils.

We and our children are going to stay here.

Do not remain near. Go! Go!"Then the families climb into the house, take their allotted rooms and set to work to build the fireplace--four posts, a shelf and a box of mud and ash beneath. Not till this is finished do they feel the house is really theirs, to be their home for another two years, till it in turn begins to collapse, or grows too filthy for even their modest standards, and again a move takes place.

Here in the hills we have left the Burmese behind, for the lords of the land chose the easy life of the plains and left the hill country to less fortunate races. Burma has ever been a land of many races, and as you climb the hills between the mighty rivers, you will find the subject races living a primitive life in little communities, far from the beaten track.

There are the Kachins far in the North, a fierce and warlike people, who quarrel among themselves now that they are forbidden to fight their neighbours. There are the Chins, who tattoo their women's faces, a relic of the bad old days when Burmese warriors [50/51] used to steal them. There are Talaings, once masters of the soil; the Wa, who hunt for scalps; Shans, who cling to a degraded Buddhism. And there are Karens, who have given the most wonderful response to the Christian message of almost any tribe in the world. Missionaries whose hearts are tempted to grow weary amid the careless indifference of the Burmese, laugh and brace their shoulders as they turn to the hills, for here are people who do not spurn their message, men who have lived all their life in the darkness of fear and who turn, as children awaking from a bad dream, to the light of Christ.

When an educated Karen was asked what he considered the chief characteristic of his race, he replied at once, "We are a people who can be afraid."

He could not have hit the nail more squarely on the head, for all the other qualities of the Karens spring from this, or have been deeply modified by it. They are shy and cautious and never let themselves go. They are secretive, as if afraid of giving themselves away. They are affectionate among themselves, faithful to their friends, but very chary of making new ones. They are kindly and patient, slow in thought and slow in act, but ready, dike the tortoise who raced the hare, to make dogged efforts if they see the goal. Sometimes they even dare to show a gleam of humour, but a life of fear is hard soil for seeds of fun to grow in, and joy is one of the flowers that Christianity must help them to cultivate.

[52] Their fear has a double root. When the Burmese became masters of the land, they bullied the subject races. If a Karen dared to drive his bullock-cart through a Burmese village, he was greeted with stones. When travelling, he dared not sleep at night, but rested against a bamboo pole, and only lighted a fire if there was a mist to hide the smoke. His good land was taken from him, and in fear of his life he fled to the hills, to scratch a living out of the rocky hillside rather than brave persecution in the plains. Since the British came, the Karens have dared to come down again to the edges of the plains, and whole villages have settled in the Delta country of the South. But the iron has entered into their soul, and it will be many years before they lose their sense of inferiority and take their place as equals beside their former oppressors.

But deeper than any fear of people is the fear of evil spirits, which haunts them from the cradle to the grave. While the Burmese followed the path of Buddha, the hill tribes worshipped devils. In every village and paddy field, there are little shrines to the hats, or spirits, who hover around, for ever waiting to pounce on those who forget to honour them. If there are any good spirits, nobody troubles to remember them, so intent are they on warding off the evil which the devils are waiting to inflict.

It is a terrible belief, and the only way to realise how terrible is to think of all our foolish little acts of [52/53] superstition, and imagine what life would be like if we really believed in them. What if walking under a ladder sent us racing home to crouch indoors for seven days, terrified that the ladder-devil would kill our mother if we dared to set foot out of doors? What if the sound of a falling picture sent us post-haste into the country to find special twigs to burn on the front doorstep, so that the picture-devil should not spirit away the soul of our new little sister? What if the sight of the new moon through glass sent us, in borrowed clothes, to the bank to transfer our money elsewhere, and kept us away from the office till the moon had waned, so as to dodge the robbery and murder with which the devil threatened us? It would not be very easy to laugh and grow fat under these conditions, if the fears were all as real as a small child's fear of the bogey that lives in the dark.

That is the sort of horror that dogs the Karens, and it makes life not only a very terrible, but a very complicated affair, because of all the elaborate ceremonies with which they try to dodge the devils. Of course the details vary among the different tribes, but the idea is the same and the weight of fear is the same.

When the little brown baby first makes his appearance in the bamboo house in the jungle, a string is tied round his wrist to prevent his kla (spirit) from escaping. His mother and father must eat their rice roasted, not boiled, and his mother's first act when she goes down the bamboo ladder must be to turn up [53/54] earth with a hoe so that the child shall not grow up lazy.

Out on the hillside grows the jungle, and a plot must be cleared before the paddy season. Home comes the father with a lump of soil from the place he fancies, sleeps with it under his head and dreams his dreams. If they are bad, he tries again; if good, he kills a chicken, scrapes its bones to see how they are marked, and if their message, too, is good, his plot is considered chosen. He burns the jungle, his eyes gleaming with pleasure at the cracks of the exploding bamboo, and when the rains come he begins his planting. When 'the green shoots sprout, he builds a platform on six legs, and with offerings of rice and liquor, and the blood of sacrificial fowls, he invokes the spirits:

"Let this cool you and please you, Lord of the hills. Lessen the heat of the soil and make the paddy good. May we work and eat until the task is finished, and let not sickness overtake us. O Guardian Bird of the field, let nothing eat the paddy in the plot where you keep watch."

When the paddy is reaped, threshed and stored, again the spirits must be remembered, and no one would dare to take the grain home for food till offerings of earth and rice and liquor have been laid, with thanksgivings, in the barn.

[55] When people are sick, all sorts of strange offerings are made. Sometimes rice balls are laid in a basket, and taken, with a chicken tied on, across two ridges of hills. There it is left with a prayer to the spirit, who caused the sickness, to go back to his own place. Sometimes two roasted fowls are set on a tray at the head of the stairs, with rice and apple leaves and a lighted candle. A cotton thread is stretched down the stairs to help the sick man's spirit to return, and when the family has been sprinkled with water and the kla summoned, the thread is broken to prevent its escape again. When at last the kla escapes in death, water and betel-nut are laid by the body to give it happiness, and sometimes the beak, wings and legs of a duck are put there too, with the prayer:

"Let the beak become a canoe for him,

Let the wings become his sail,

And the legs his paddles."Apart from this continual remembering of the spirits, life is a simple affair. There is the bamboo house to be built every two years or so, sometimes one huge one for the entire village, sometimes separate family ones copied from the Burmese. A few pots are needed for cooking, mats to sleep on, bamboo joints for fetching water and implements for paddy-farming or fishing. Somewhere in the house a primitive loom is rigged up, on which the women weave cloth for clothes and blankets. They are tough and strong and last a lifetime, for as the Karen usually wears his [55/56] entire wardrobe on his back, there is little temptation to shorten its life by washing-days.

Everyone wears a loose smock of varying lengths, and the women have a skirt also. Their smocks are often trimmed with coloured threads or white seeds sewn on in intricate patterns, and sometimes strings of beads or circlets of rattan or brass add to their charms. The queerest fashion of all, found in one of the tribes, is to have rows of brass rings round the neck, the more the merrier, till the unfortunate woman has a neck like a giraffe and needs a special bamboo pillow to hang her head over at night. When the rain comes (and it does come in Burma!) people carry palm-leaf umbrellas, or wear raincoats of thatch under enormous hats that make them look like mushrooms. They have to spend half their life, then, in little canoes dug out of hollow tree trunks, for the valleys turn into lakes and only the trees are tall enough to keep their heads above water.

When a young man wants to choose his bride, he is free to serenade her with harp and verse, and she may reply in song and invite him in, but all the formal marriage proposals are made through a "go-between." Curiously roundabout they sound to Western ears.

"Give me a white pullet and I shall feel better," says the messenger to the girl's parents. And if they have two daughters, they reply, "Have you come for a basket of rice, or only for a mortarful?"

Of course the omens are consulted, but apart from [56/57] that there is no actual marriage ceremony. The bridegroom is brought with song and dancing to the house of the bride, where the nuptial feast is held, and there as a rule he makes his home.

There is one very curious taboo among the Karens. If anyone mentions his father or mother by name, he is thought to be wishing their death. Even a husband will speak of his wife as "the mother of Bo-Sa" rather than call her his wife. You can imagine the awkward moments when a missionary schoolmaster is trying to make out his lists, or a Karen clerk is commanded to put his parents' names on a Government form.

The first Christians to start a mission among the Karens were the American Baptists, urged on by Dr. Judson, one of the most heroic missionaries of the last century. He bought a bandit condemned to slavery, and with incredible patience taught him to read and trained him as a Christian. Baptised and eager to spread his new Faith, the man returned to his own people with a white missionary. Then an amazing discovery was made. The Karens had an ancient legend, which told them that one day a white brother from across the seas would come and restore to them a Holy Book which they had lost long ago. They welcomed this "white brother and his Holy Book," and as they listened to his teaching they grew more and more convinced that the prophecy was fulfilled, for though they knew nothing of a Saviour, Christ, [57/58] their legends told them of a God called Y'Wa who made the world and taught men wisdom.

No one has ever discovered where this legend came from, or how the Karens got their dim tradition of God. But certain it is that the stories they remember are amazingly like the beginning of Genesis.

"When first the earth was formed," they say

"It was Y'Wa who formed it.

Y'Wa is eternal; He alone existed

Before the world was made."Then, in picturesque language, follow the stories of man's creation, of "woman made from a rib of man," of an orchard with seven kinds of fruit, and of Y'Wa's command to leave one fruit untasted. The Devil appears as a mighty serpent, tempts the woman, the fruit is eaten and Y'Wa appears to lay his curse of death on the sinful pair. In terror, they turn to the Devil for help, and from him learn to make sacrifices and offerings, and to use chicken bones for omens.

The book from which they learnt all this was brought, they say, by a white man. But it was lost, eaten by fowls and pigs in a paddy field, and all that remained was their certainty that one day a white brother would come again, bringing their lost treasure.

The white man has come, bringing his sacred book, and the Karen has turned to him with joy--not the spontaneous, light-hearted joy of a happy [58/59] people, but the cautious, timid joy of a people bowed down by fear, who scarcely dare to believe that deliverance is at hand. But little by little, they are learning to turn their back on their fears and a marvellous new life is opening for them. The man who used to run home in terror if a snake of evil omen crossed his path, now dares to board a train to take his child to hospital. The man who helplessly sat down to starve if his paddy crop failed, now makes experiments with arrowroot. And the man who shivered on his mat, haunted by fear of devils, now dies with a smile on his face, content to trust in Jesus.

"Behold I make all things new." Read on, and you will see the promise coming true.