|

|

|

|

Chapter I. Childhood--School and College Life--Curate and Vicar, 1844-1884

Chapter II. First Year's Survey of the Diocese

Chapter III. First Visit to Nyasa, 1885

Chapter IV. The Third Year, 1886

Chapter V. The Fourth Year, 1887

Chapter VI. The German Occupation, 1884-1888

Chapter VII. The Insurrection, 1888

Chapter VIII. The War and the Anglo-German Agreement, 1889

Chapter IX. The Nyasaland Protectorate, 1889

Chapter X. In England, 1890

Chapter XI. The Division of the Diocese, 1891-1892

Chapter XII. The Last Year's Work, 1893

Chapter XIII. Last Illness and Death, 1894

PREFACE SOME apology is due from me to the kinsfolk and friends of Bishop Smythies, who, shortly after his death, entrusted to my care the preparation of the story of his life. I owed the honourable trust, probably, to the fact that a very intimate friendship bound me to the Bishop. He cared for me, I think: I know that I loved him, and with a love full of veneration and gratitude, so that it was a joy at all times to serve him. Such an affection for a friend is not a bad qualification for the task of telling what that friend was and did. It is the pledge of many things, yet has its limitations, as I ought to have known and now have learned. The best will in the world cannot make the day longer, nor can it give the power, if a man has it not in some degree already, of using for continuous work scraps of uncertain leisure in a life of many interruptions. And so it came to pass that at the close of last year- three years and a half after the Bishop's death--I found myself with my task still on my hands, and still far from completion. The documents had been collected, copied, and arranged, but only the first chapter was actually written, and how the remaining chapters were to be done I could by no means tell.

At this point of my perplexity, to my great satisfaction, help appeared, and from the best possible quarter--from Africa itself. In October 1897, Miss Gertrude Ward, a member of the Universities' Mission, serving as nurse at Magila, was sent home by the doctors to recruit after repeated attacks of African fever. The air of England proved so excellent a restorative that in February of this year I felt that I might without scruple appeal to her to take up and complete the task in which I had practically failed. I knew her competence--indeed all readers of African Tidings know it--and she had lived among the peoples among whom the Bishop lived. Miss Ward most kindly gave up for this a large part of her holiday in England. The result is in the reader's hand. With the exception of Chapter 1. all is Miss Ward's work, and so careful, so skilful was the workmanship that almost nothing was left for an editor to do, save to approve. I hope the Bishop's friends will count my failure pardonable, even a 'happy fault,' since the delay has in the end brought to this memorial of the Bishop more things and better things than I had power to give.

A complaint has been made against historians that they leave us, for the most part, to imagine how their heroes 'were housed and clothed, what was their manner of speech, and how they filled up the blank intervals of time between their mighty deeds.' [Lotze, Microcosmus, ii, I.] And the complaint is a just one; for these and like details of everyday life bring us into relation with the doer of the mighty deeds, with the man himself, and it is the man himself that we really long to know. He is, if only we can get at him, far more interesting than his deeds: in truth the best of him may often remain unexpressed in deeds; he has lacked opportunity or has been thwarted by circumstance. We ask therefore of the historian, and in particular of the biographer, that he shall tell us not only the story of the acts and achievements of his subject, the 'stout and gallant deeds' which he wrought en grand costume--in full dress--upon the public stage, but also the story of his common days, in the undress of familiar life, and how he impressed those with whom his life was cast. Deeper yet, the writer will earn our gratitude who can show us something of the inner, spiritual life of his hero, the life which is the man himself, and from which all his real influence has issued as from a springing well. A careful reader will find, I think, a good deal of this kind of information, by glimpse and suggestion, throughout the following chapters. In the communications from the late Bishop Maples, the late Archdeacon Jones-Bateman, and Mr. Dale, he will find something more precise. These men had exceptional opportunities for observing the Bishop: they saw him under the most varied conditions, and under the most trying conditions not only at his best times, but at his worst; wearied to death, stricken with fever, or a prey to the strange tricks which the East African climate plays upon the European mind. Their testimony is exceptionally valuable. In comparison with their opportunities of observing the Bishop my own were small--they were restricted to his visits to England, when, to my happiness, he was wont for a time to be my guest. Even in this narrow area of observation some things have come under my notice which may contribute to the more defined, more complete portraiture of the man himself. I will therefore set them down as simply and as truly as I can.

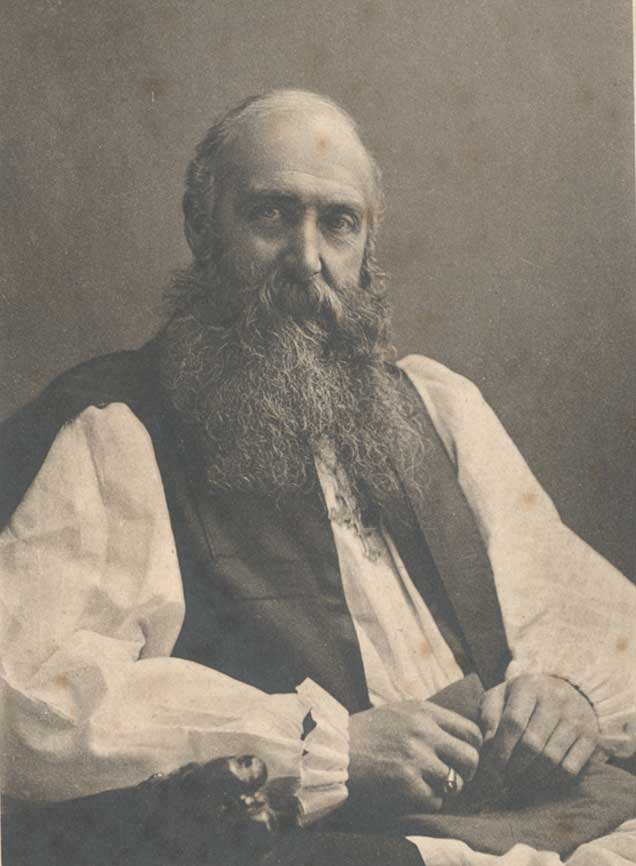

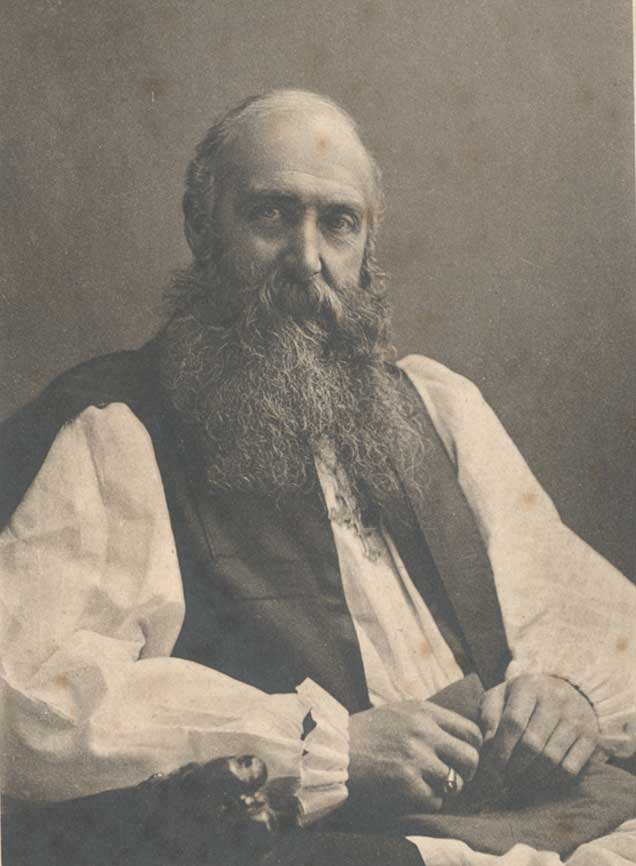

Those who met the Bishop for the first time were struck at once by his commanding presence; not his stature only, but his stateliness, a manner dignified and courteous and singularly gracious. A glance at the frontispiece of this book will help those who never saw him to understand this. In height he stood about 6 feet 2 or 3 inches, but his well limbs and body took off all appearance of tallness or burliness. An American bishop who met him at the Lambeth Conference said of him, in a sermon preached at Washington, 'He was one of the manliest men I ever looked on--the picture of manly beauty--a face loving and gentle as that of St. John.' This blending of strength and gentleness in his face and manner has been often noticed, as for instance by Canon Scott Holland, who once in public spoke of his 'imperial meekness,' his 'superb benignity.' No one who has seen the Bishop will count the description, with its seeming incongruities of attribute, an exaggeration or a paradox.

This fine physique was all that it seemed to be. Few men could equal his powers of work and endurance. Even in his curate days at Roath his walking won the admiration of his 'boys.' One of them describes his walks in terms which might stand for an exact description of his later 'form' on the great journeys to and from Nyasa: 'With head in air and in incessant movement to this side and that, keenly observant of every passing thing, he strode ahead of us like a war-horse.' A fortnight spent with him in Cornwall, on the occasion of one of his visits to England, left with me a profound conviction of his unusual powers, and also, I may say, some sympathy with the companions of his travels. He seemed never able to pass a hill without climbing it, partly, I think, from a certain inward satisfaction at overcoming difficulty, but chiefly from the delight he took in the wide outlook and sense of space which are to be had only on the heights.

This amplitude of nature was traceable all through the man, within as well as outwardly. Everything was on a big scale, in generous measure, as if in view--as no doubt it was--of the exalted place that he was called to fill. Faber speaks of St. Vincent de Paul as the 'saint of wide-open arms, and heart capacious as a sea.' I do not wish for a moment to compare the Bishop with that great saint, but I can honestly say that I never knew a man who came nearer to this description of him. Men of very varied character and views felt themselves, at first touch, in easy, friendly, trustful relation with him. His voice and manner and whole aspect seemed to welcome them. None felt this more than those critics of great discernment in this matter--the children. They had no awe of this big man, and never scrupled to demand his entire attention to their small concerns. There was room, too, in his heart not only for those who shared his faith, or had no faith at all, but--a harder thing--for those whose faith and methods were cast in a mould very different from his own. He could be happy with such persons, really admire their zeal and the good results of their work, and, so far as he could without sacrifice of principle, he helped them. Among his papers I find an acknowledgment of a donation to the Salvation Army, and the last cheque he ever drew was in favour of the Bible Society. His work at home generally included a visit to Ireland. It will be a surprise to some to know that his preaching and speaking were greatly appreciated there. The generous Irish people, at least the 'Church of Ireland' people, are not always so tolerant towards ecclesiastics so pronounced. What favour he won was won honestly and never at the cost of compromise. 'I cannot play the Protestant,' he said; yet he could, and did without pretence, find much in common with many who pass under that elastic name. If they loved the Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity, it was passport enough.

It is not my purpose to 'edit' my friend, but to make him known as I knew him; so I take note here of a point which may seem at variance with my claim for him. It has been said that the Bishop showed at times towards those who worked under him a certain imperiousness of temper, an impatience of contradiction and intolerance of opinion that differed from his own. It is not without interest to note that precisely the same charge was made against another great African prelate who had many characteristics in common with our Bishop--Cardinal Lavigerie. There was probably a measure of truth in the charge in the case of both. 'Je suis Basque,' said the Cardinal, 'et, ce titre, entêté lorsqu'il le faut.' And Bishop Smythies was wont, in his own case, to acknowledge something more than obstinacy--flashes of quick temper, some over-severity of rebuke, an irritation with prejudiced or slow-moving minds. These things did not happen often, but they did happen, and the Bishop sincerely deplored them, and on occasion would apologise for them with pathetic penitence. One who knew him well in the Roath days said of him, 'Charles Smythies was not naturally a saint, but a man with all a man's difficulties. He fought his way to the front, into calm, into maturity, by dint of sustained hard work.' The old nature lived on beneath the new, chained but not dead, and there were moments of revolt, not easily or always quelled. Also it should not be forgotten that he was set to govern, and authority must not be, so Bacon teaches us, 'facile,' yielding lightly to persuasion. He could be stern, no doubt, but behind it all there lay real tenderness, an almost womanly tenderness, that needed often but a word to fill his eyes with tears. I do not think that the Bishop could have gained his long, deep, immovable patience with the wild African nature at any price short of this bitter struggle with himself. [More skilful in self-knowledge, even more pure, / As tempted more.'--Wordsworth.]

Of his courage there is no need to speak; the evidence of it is plain enough throughout the book. Mr. Coles once asked him if he ever felt any fear of the wild beasts. He replied, 'Only once, when I got separated from the bearers' (on the way to Nyasa), 'and for two or three days we had to live on some lemon-drops, and the wine I had to celebrate with. Then I got weak, and when I heard the creatures it affected my nerves, but never at any other time.' Under even the most disconcerting circumstances he never seemed to lose his self-possession, not even at Potsdam, at the German Emperor's levee, when through out the evening, in the midst of a brilliant throng of notabilities, he was doomed to carry everywhere his tall black hat!

In his work as Bishop, apart from the government of his huge missionary diocese, he laid most stress, I think, upon his teaching office, and next to that upon the work of the education of the native ministry. He had learned from the Gospel that the mission of a Bishop was not only to shepherd but also to feed Christ's sheep and so he set himself to teach and preach and speak incessantly. In England he almost never refused an invitation to preach, if a free time could be found.

In the ordinary sense of the word, he would not have been called an eloquent preacher, but he was certainly a very forcible, very impressive, very persuasive preacher. As you listened to him you felt all the while that here was one whose chief concern was not so much with his ideas as with you; there was no research after choice words, or any of the common tricks of rhetoric, or any thought about himself; but simply the urgent desire to impart to you some spiritual good. He took no pains about the style and garnish of his sermons; he had not the time for this, even if he had the will. ['A great many preachers die of style that is, of trying to soar; when if they would only consent to go afoot, as their ideas do, they might succeed and live.'--HORACE BUSHNELL.] As a rule, about half an hour spent alone was all the 'proximate' preparation he could give. His subject naturally few in number, had become by frequent repetition very familiar to him they were well in hand, and all he needed was to gain the grace of God to make his words profitable to those who heard him.

Whatever qualifying word should be used about his preaching, there is no doubt that, as a platform speaker upon missionary subjects, he was excellent. He had the art of putting things in a very genial, interesting, and attractive way. And then his hearers knew that he who was asking them to give their life or goods for the great cause, had himself given all he asked. [The income of the Bishopric of the Universities' Mission was 300l. a year. Of this Bishop Smythies, during the ten years of his Episcopate, never kept a penny, but returned all to the Treasurers of the Mission.] The aureole of sacrifice was about his person and his words, and made them exceedingly persuasive. At the great meeting of missionary bishops at St. James' Hall, at the time of the Lambeth Conference, no one was listened to more attentively or received more enthusiastic applause.

Apart from his study of Scripture and theology he read not much, and a book lasted him a long time. Of novelists his favourite was Marion Crawford, but a novel never really captured him. As a rule he preferred to make, first-hand, his own studies in men and manners, his own 'criticism of life.' Hence the 'give and take' of social intercourse were to him, as a rule, more really informing, more entertaining, and a more real refreshment than a book.

Of all the works of the Mission the one that had, perhaps, the most cherished place in his heart was his work with the native ministry. He felt that the future of Christianity in East Africa lay with them, that Africa could only be really won to Christ by Africans. For a time a European clergy must occupy the ground, and help in the discovery and the training of those among the natives whom God is calling to the priesthood. But their work is only a temporary expedient, beset with many, almost insurmountable, difficulties--the difficulty of understanding and being understood by the native mind, the difficulty of climate, the inevitable expense of maintenance and such-like. He looked for the rise of an African Church, complete in its organisation and independent; all its sacred offices, from the highest to the lowest, filled by Africans, and its rites more rich and more adapted to the African nature than our own. His favourite resting place was his room, an upper room in the College at Kiungani, with a beautiful outlook over the sea on to the distant shore of the mainland. Here, surrounded by the young native teachers and the young aspirants for holy orders, he found his most delightful employment. He had them incessantly about him; he watched and tested their vocation, lectured to them, supervised and helped them in their studies, and guided them in their moral and spiritual life. At a public meeting in London, one of them, now a priest, speaking of his bishop, said, 'You call him," My Lord"; I call him, "My Father" and the name expresses precisely the happy relation of mutual affection and mutual service which existed between these keen, intelligent young natives and their spiritual chief. The last act of the Bishop in Africa was, on the morning of his departure from Zanzibar, to send for the four natives who were shortly to be ordained. He was then in hospital, and they knelt by his bed--his death-bed; he had a word for each, and then he blessed them.

I cannot bring myself to speak of the inner spiritual life of the Bishop, though of course it stood as root to all he did, to all that men saw and wondered at in him. Of that inner life St. Paul has said that 'it is buried out of sight with Christ in God;' there it is best left, or rather it is best for me to leave it.

Of his spiritual habits, I have nothing singular to record. He was most careful to secure at least the first two hours of each morning, before the day's work began, for communion with God. In this time he celebrated the Holy Eucharist, made his Meditation, and said the Morning Office. This was hi minimum of necessary provision for the day, and he was extremely unwilling to allow anything to interfere with it. During his stay with me I served him every morning at the altar of our church, and learned from him with what profound reverence and recollection a priest should accomplish this, the most sacred action of his ministry. That our Lord was present, really, truly, and substantially, in His Sacrament was one of his deepest and most cherished convictions, and in that Sacrament he found a never-failing source of strength and consolation.

It is not surprising that in a life so beset, so full of affairs, and in such incessant movement, he should feel the absolute necessity of an occasional escape into solitude and silence.

He shared Vinet's conviction that to be incessantly occupied with matters directly or indirectly spiritual does not by any means of necessity make a man spiritual. Indeed, it were nearer to the truth to say that the result may very easily be the reverse of this. What is habitually said or done becomes in time automatic--it can go on independently of our volition--and this in spiritual things is fatal. As a measure of self-protection the Bishop, not content with his annual Retreat, was wont from time to time to disappear into some religious house, there in quiet to review his ideals, his methods, and motives, and to refresh his sense of the unseen, eternal things.

I dare not hope that this little Memoir will satisfy the love of those who knew the Bishop. In their memory he lives as something greater, nobler, more lovable--more human, more divine--than all that we have told of him. This is inevitable. How can we recapture and detain in words a life that has gone from us, especially a life so full, so rich, so fine as his? These men of God are His good gift in particular to their own generation; they bloom for their hour, then disappear, but their influence remains merged in the c stock, interfused through the common air, antiseptic, quickening, fragrant. Let us thank God that He has given to our own time, in the person of Charles Alan Smythies, a great missionary, one of the manliest of men, a deeply religious and entirely fearless Catholic Bishop.

E. F. RUSSELL.

ST. ALBAN'S, HOLBORN, November 1898.

Project Canterbury