THESE thirty years of transition have been a period of steady expansion and development, of very remarkable progress. With ever-increasing earnestness the problems within the Church and outside it have been faced, and, with the limited means available, everything possible has been done towards the solution of these problems.

Geographically, the work in Nigeria falls into three clearly defined sections: (i) the Niger itself with the country to the east and west of it; (2) Lagos and its hinterland, including the Egba, Yoruba, Ijebu, and Ijesha Countries; (3) Northern Nigeria. With all these areas the readers of the preceding chapters are now familiar. We must survey them one by one.

I. THE DIOCESE OF THE NIGER is Crowther's old diocese, greatly extended and developed. We have already seen how, after the troubles of the early 'nineties, the churches of the delta elected to form themselves into a semi-independent "Delta Pastorate," staffed entirely with African clergy, but recognizing the authority of the bishop. It developed into an archdeaconry, with Archdeacon D. C. Crowther, as its superintendent, and later with Bishop Johnson in episcopal charge.

The work along the river, north of the delta region, was created an archdeaconry by Bishop Tugwell and staffed by both African and European clergy under his own direct supervision. So remarkable was the growth of this section that in 1919 (on the advice of the bishop) it was separated from the Lagos-Yoruba section and constituted a separate diocese. An African assistant bishop, the Rt. Rev. A. W. Howells, was consecrated in the following year to assist Bishop Tugwell, more especially in the supervision of the delta region. In 1920, Bishop Tugwell, after twenty-eight years of magnificent service, resigned, and was succeeded by the present bishop, the Rt. Rev. Bertram Lasbrey, with the title of the "Bishop on the Niger."

Onitsha, the first station of the Niger Mission, is to-day the head-quarters of the diocese. In addition to the residences of the bishop, the secretary (who is also the archdeacon), the treasurer, and the general manager of schools, there is one great church with a regular congregation of 1000 Ibo Christians, two smaller ones, and a fourth for non-Ibos, the Dennis Memorial Grammar School, large elementary schools, and a bookshop. The visitor is at once impressed by the very prominent position the mission holds in the town. As the population is not much more than 16,000, it is possible to exert a greater influence than in some of the much larger towns of the Yoruba Country. Five miles to the east, at Iyi Enu, on the main road along the river, is the mission hospital, the ninety beds of which usually accommodate between 700 and 800 patients each year, there being in addition some 20,000 outpatient treatments. The hospital is staffed almost entirely by women, European and African, and a great deal of its activity consists of maternity and child-welfare work. Five miles beyond the hospital is the St. Monica's School for girls, with about 170 boarders. All these things combine to make Onitsha a really strong base for the Mission.

About twenty miles east of Onitsha, on the great main road marked out with telegraph poles and wires, is the country town of Awka. This also is an important mission station, one of the most important of all, for it includes the training college for the whole diocese. This modern "school of the prophets" stands on the very spot that thirty years ago was "bad bush," i.e. a sacred fetish grove where the unholy rites were performed and where the bodies of twin babies and human sacrifices were thrown. It is a thoroughly well equipped institution, with a staff of three English and two African graduates and an African deacon. There are usually about ninety students in residence, training as ordinands, catechists, and teachers. At Awka there is also a girls' compound, a school for training the older girls for the duties of life as wives and mothers in African homes.

Forty miles north-east of Awka is the town of Enugu, on the railway, destined to become a place of considerable importance, for it is now the seat of government for Southern Nigeria, the residence of the Lieutenant-Cfovernor. Such a place presents fine opportunities for work among the growing European population as well as among Africans. Two miles from the capital, at Enugwu-Ng'wo, there is a most interesting station in charge of an African clergyman, the Rev. Isaac Ejindu. From here, in the heart of what used to be a cannibal country, with a population practically unclothed, he superintends with the assistance of two other African clergy a district with no less than seventy churches. At the head-quarters there is another girls' compound, a boys' farm with apprentice work (again on what was once "bad bush"), a carpentering school, and a "twinnery."

The last-mentioned is the most interesting of all, for it is an experiment for meeting the old but ever-present trouble arising from the superstitious fear of twins so prevalent in this region, and still persisting in spite of the efforts of Government to overcome it. The old custom in this locality was to put twin babies into big clay pots and throw them into the bush, and it is probable that a considerable number of little ones still perish, not because their parents lack human affection for their offspring, but because it is eclipsed by sheer terror of the evil they believe to have come upon them. At Enugwu-Ng'wo efforts are made to persuade the mothers to bring their twins to the twinnery and stay there to feed them. Motherless and deformed babies are also welcomed. It is a novel experiment, full of hope for the future and capable of development here and elsewhere.

Fifty miles south of Onitsha, in the Owerri Province, is another very important station at Ebu Owerri. So recently as 1905 a government medical officer (Dr. Stewart) was murdered in the market place of a neighbouring town in the presence of hundreds of people, and his bicycle was broken and tied to a tree to prevent it running away. [Recently Bishop Lasbrey dedicated a beautiful church erected by the people who, in their ignorance, murdered Dr. Stewart.] It was a year later that Archdeacon Dennis went to the Owerri district as the first Christian missionary to settle there. A piece of "bad bush" was assigned to him at Ebu Owerri, and a little mud house was built upon it. To-day a large church stands on that spot, with an average Sunday congregation of about 750 people. Beside it, there is a school with 500 children, clean and neatly dressed, and taught by a staff" of trained Ibo schoolmasters.

But the outstanding feature at Ebu Owerri is specialized work for women and girls, carried on by women missionaries, while African clergy look after the general, pastoral, and evangelistic work. The women's work centres round two compounds, one for unmarried girls and one for married women. The former is really a school for training brides; its pupils are betrothed girls who are too old for the village schools and come here to receive such instruction as will fit them for matrimony. Young Christian men send their fiancees to this school and pay for their food.

One of the problems of the Mission is that in many places in Nigeria the education of girls has not kept pace with that of boys, and as a result many of the catechists and teachers have to marry uneducated girls. This "school for brides" is an attempt to solve the problem, for one locality at any rate. All the girls, if qualified, receive baptism before they leave (if indeed they were not baptized before they came), and they marry immediately on leaving. The women's compound does a similar work for women who are already married. Christian husbands who have been married for several years and desire to have their wives instructed, can send them to this school. Usually the wife brings her baby and an older child to look after it while she is in class. Most of these women are unbaptized when they come to the school, for the general rule throughout Nigeria, "under ordinary circumstances," is not to baptize until the candidate can read. The women are baptized before they leave; and in a special service their marriage is blessed, and thus raised to the level of a Christian marriage, the parties promising that it shall be life-long and exclusive. In the country around Ebu Owerri there are a hundred churches in various stages of development. Twenty-five years ago there was not a single church or African Christian in that area.

The work at all these stations, and the numerous out-stations, is among the Ibo people and is carried on mainly in the Ibo language or in English.

The work of the diocese is not confined to the east side of the Niger. As early as 18753 beginning was made at Asaba, on the west of the river, nearly opposite Onitsha, and since then stations have been opened at Ogwashi-Uku and other places in the Benin Province.

More arresting, however, is a work that began a few years ago a little further south, in the Isoko district. Somewhere about 1916, while the great European war was at its height, the Isoko tribe began to stretch out their hands to God. Perhaps scarcely knowing what they were asking for, they pled for light, asked that a teacher might be given to them to tell them about the great God in Whose existence every African firmly believes. Such appeals are so frequent in West Africa that it is not always possible to respond. But in this instance the call seemed so unmistakable that an experienced missionary was sent, and the people flocked from every quarter to hear his message.

In a few years a hundred towns and villages in the Isoko Country had built churches, and a score of young men were being trained as evangelists and teachers. The opportunity was so promising that a second missionary was stationed there, for the work was too great for one man. Bishop Lasbrey wrote: "Day after day, week after week, men and women crowded into the churches and besieged the gospel messengers with requests for advice and teaching, for more light." But the senior man broke down and had to retire, and a few days later his colleague died of blackwater fever. Two more men were sent, one of them died in 1927, also of blackwater fever, and five months later the other had to be invalided home. The future of the work hung in the balance, for it seemed impossible to carry on in a mass movement area with only one missionary and one African clergyman. In his plea for reinforcements the bishop wrote:--

During the last ten years (and more especially the last seven) a great mass movement has taken place in the Isoko Country. There are now in the comparatively small area, 104 churches, many of them very large ones. Two churches alone have over 2600 regular adherents, and the total is about 20,000. At Ozora, at morning and evening prayers, every day in the week, there is an average of 900 attending, and more on Sundays. Aviara the same, and up to 1500 on Sundays. Uzere nearly as many; and other churches have very krge attendances. Yet the whole missionary strength is one man at home invalided. When a missionary goes round, he is literally besieged morning, noon, and night. In order that he may get his meals, it is not infrequently necessary to get some people to make a sort of cordon round the house to keep the folk off for a while.

The Isoko Country differs completely from the surrounding countries, in tribe, language, and everything. No other society is at work in it. For a while the situation was really critical, and it was a question whether from sheer lack of workers the C.M.S. would be compelled to abandon it, which at that juncture might have meant the people relapsing into gross heathenism. Happily, after a time the one missionary was able to return, and in 1929 two more men joined him. Great was the joy when, in the spring of 1930, the first two women missionaries arrived. They were met some miles from the village and escorted by hundreds of African Christians with drums and bells and decorations. Medical and social welfare work was at once undertaken, and African girls are being trained as nurses and midwives.

This is an opportunity of unusual promise, but such a mass movement creates all those problems we have referred to in previous chapters. Without effective oversight and thorough training there is sure to be disaster. We rejoice over it with trembling; but if proper pastoral, educational, and training work can be undertaken and maintained on a sufficiently wide scale, it may yet prove one of the most glorious chapters in the history of the Niger Mission.

Among the numerous creeks and waterways of the Niger delta is the other archdeaconry of the diocese, that known as the Delta Pastorate. This also has made considerable progress. It has its centre at Port Harcourt, Archdeacon Crowther's head-quarters. The mention of that veteran's name compels us to pause for a moment to pay tribute to the long and distinguished services he has rendered to the Kingdom of God. In previous chapters we have seen him as a boy accompanying his father, as a young clergyman taking responsibilities, and in his mature years leading and guiding the churches of the Delta Pastorate. It is just sixty years since his father ordained him. To-day, an aged man full of honour, and "venerable" in the highest sense of the word, he is still in full work and devoted to the cause in which his whole life has been spent.

Archdeacon Crowther has seen the work in the delta region grow, from the first mud-and-thatch church at Bonny, until to-day it comprises eleven districts, with an average of nearly sixty churches in each, and all self-supporting. Unfortunately these districts are understaffed, some having no resident clergyman, which inevitably is a source of danger. There is no C.M.S. European missionary stationed in this area, except at Port Harcourt, where an Englishman has charge of the book depot and does a measure of prison and leper work.

The progress of the Delta Pastorate may be seen in a notable event at the beginning of 1929, when Bishop Howells dedicated a magnificent new church at Okrika, on a small island in the river not far from Port Harcourt. In preaching the dedication sermon, Archdeacon Crowther recalled the time when he first went to Okrika and found it dominated by a great juju house which rose far above all the other buildings. It was a place feared by strangers because of the deeds of darkness with which it was associated. To-day the juju house has gone and the new church, which seats 1500 people, has taken its place as the most prominent building in the town. The principal chief, instead of presiding over the old heathen rites, was interpreting the Archdeacon's sermon. It was a great occasion, and Christians gathered from near and far. For three days before the ceremony, from forty to fifty canoe loads of visitors arrived. Never before had there been so many people gathered there, or with so much rejoicing. For the dedication service, it was estimated that at least 2000 people were packed inside the church, and there were quite as many outside, unable to squeeze in. The church was entirely paid for by the people, without outside aid. On the following day, Bishop Lasbrey conducted in the new church the biggest ordination service ever known in the diocese. Ten men were admitted to deacon's and four to priest's orders.

The chief weakness of the Delta Pastorate is the very inadequate provision for training. There is an institution at Ihie for the training of catechists, under an African principal, but it only accommodates thirty, and needs to be enlarged and strengthened if it is to meet the needs of the situation. The candidates for ordination go to Awka College for training.

After nearly forty years of separate and independent existence, the Delta Pastorate is now organically joined to the C.M.S. portion of the diocese. Under a new constitution, the two archdeaconries are welded together in one synod that has authority over both. This is a healing of the old wounds of those dark days in the 'nineties, which is a cause for devout thankfulness. Both sections of the diocese stand to benefit by the drawing together. Co-operation and the pooling of experience must inevitably be for the greater good of the whole.

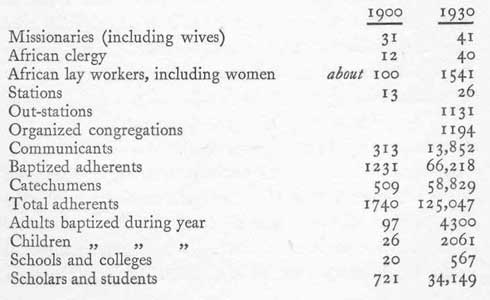

The following statistical table will give some idea of the growth of the Niger Diocese in the thirty years:--

Missionaries (including wives) 1900, 31; 1930, 41

African clergy 1900, 12; 1930, 40

African lay workers, including women about 1900, 100; 1930, 1541

Stations 1900, 13; 1930, 26

Out-stations 1900, 11; 1930, 31

Organized congregations 1900, 11; 1930, 94

Communicants 1900, 313; 1930, 13,852

Baptized adherents 1900, 1231; 1930, 66,218

Catechumens 1900, 509; 1930, 58,829

Total adherents 1900, 1740; 1930, 125,047

Adults baptized during year 1900, 97; 1930, 4300

Children 1900, 26; 1930, 2061

Schools and colleges 1900, 20; 1930, 567

Scholars and students 1900, 721; 1930, 34119

II. THE LAGOS DIOCESE has made similar progress, first under Bishop Tugwell, and, since the separation from the Niger Diocese in 1919, under the present bishop, the Rt. Rev. F. Melville Jones, who previous to his consecration had spent twenty-six years in the Yoruba Country, chiefly as principal of St. Andrew's College at Oyo.

Lagos, the most important port in British West Africa, is the head-quarters of the diocese. Its population is considerably over 100,000, which works out at 4414 persons to the square mile. Less than 1200 of the inhabitants are Europeans. In such a town the C.M.S. naturally occupies a most important position, having a number of churches, schools, And other institutions.

Most important of all is the cathedral which stands in a prominent position on the Marina. For many years known as Christ Church, it is now being reconstructed, and has already been extended by the erection of a large and beautiful choir, so that it may be worthy to be the cathedral of the diocese. The foundation stone was laid by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales in 1925, and the enlarged building was consecrated in June, 1929, by Bishop Melville Jones and his assistant bishops, the Rt. Rev. Isaac Oluwole, and the Rt. Rev. A. W. Smith. It is intended to rebuild the nave on a scale to correspond with the choir, and when the scheme is completed the Lagos Cathedral will unquestionably be the finest church in West Africa. It is fitting, and not a little significant, that it has been designed by an African architect and built by African contractors. Within, its most conspicuous feature is the east window, a memorial to Samuel Adjai Crowther, slave, pioneer missionary, and bishop. Practically every part of the diocese took part in the erection of the cathedral; tens of thousands of African Christians contributed to it in one way or another, and communities or individual donors have given the furniture and fittings. It was opened and consecrated to the service of God with overflowing joy and highest expectation as to its value as the spiritual centre of the diocese.

But notable as the cathedral is, it is only one feature of C.M.S. work in Lagos. An English church for the use of Europeans is in charge of a chaplain. The Grammar School was founded in 1859 and has now some 450 pupils. Many of the leading men of Lagos received their education in it. The girls' school, founded in 1869, has about 300 scholars. One of the most remarkable features of all is the great bookshop that provides literature of all kinds for all branches and departments of the work. The head depot is one of the largest shops in Lagos, dealing in every kind of literature and general stationery, and it has seventeen branch depots spread over the diocese. It is essentially a piece of missionary work, carried out on strictly business lines, under the direction of a lay missionary, Mr. C. W. Wake-man, who has given twenty-five years to the work. All the profits of the bookshop are devoted to the Mission.

While dealing with Lagos, we cannot omit mention of one devoted leader who resides there, the aged assistant bishop, Isaac Oluwole. Ordained in 1881, and consecrated assistant to Bishop Hill in 1893, he has rendered noble and most distinguished service, and now in old age he is loved and honoured by all.

Travelling into the interior by the railway, we find the country dotted over with C.M.S. stations and outposts. The oldest of these, Abeokuta and Ibadan, we have dealt with at length in previous chapters, and from them the work has spread far and wide. Between the years 1915 and 1918 important new extensions were made, e.g., Evbiobe (Benin Province) in 1915; Benin city, 1917; Ilorin, 1917; and Warri, 1918. The last named acts as a link with the Niger Diocese. Abeokuta and Ibadan are strongholds of the Church, and so are many smaller towns. In the Egba and Yoruba Countries all the churches are under the pastoral care of African clergy and lay workers, and all the European missionaries are set apart for special work.

As a mission centre, Oyo, the capital of the Alafin, who is nominally "King of all the Yorubas," is second only to Lagos in importance, for it is the training centre for the diocese. St. Andrew's College, founded in 1896 by the Rev. F. Melville Jones (as he then was), and directed by him until his elevation to the bishopric twenty-three years later, is by far the most important institution in the whole diocese. Under the principalship of Archdeacon Burton, it has made rapid progress and has now a staff of six Europeans (four of whom are graduates) and thirteen Africans (two of them graduates). The students in residence usually number nearly 180: ordinands, n; catechists, 12; normal, 155. The normal students take a four years' course. The ordinands are at Melville Hall, a new building erected in the spacious compound a few years ago and called after Bishop Melville Jones, the founder. The men come for training from all parts of the Yoruba Country, and even from places as distant as Benin and Lokoja. Quite recently there were 132 candidates for thirty vacancies. The value of such an institution is inestimable.

The other special educational institutions in the diocese include boys' grammar schools at Abeokuta, Ibadan, Ijebu Ode, and Ondo, and the girls' school at Ibadan with two women missionaries in charge; a diocesan girls' school at Ijebu Ode in the Ijebu Country; and a girls' training class at Akure, in the Ondo Province. The last mentioned is doing a very useful work for girls who want a thoroughly practical and chiefly non-literary education. Two European women are in charge, and it is the centre for girls' work in the whole Yoruba Country. Girls come long distances for training. Such subjects as weaving, gardening, and farming are included in the curriculum. In connexion with it, a nursery school has been started with the double purpose of saving babies' lives and of training girls in all that pertains to mothercraft.

An experiment was made lately in holding a training school for mothers. They gathered at Oyo for five days. A distinguished African medical man, Dr. Oluwole (son of Bishop Oluwole) gave health lectures, and several women missionaries also took part. It was so successful that it clearly points to possibilities of new usefulness that should be developed as soon as possible. It would be much easier to do such work in an area like Onitsha, where women medical missionaries are available to take charge of it and give the lectures. Unfortunately the C.M.S. has no medical station in the Yoruba Country. A women's guild is very strong and is serving a most useful purpose. In connexion with it a women's central conference is held every year, at which instruction is given in matters of health and personal and social hygiene. The women themselves take part in the conference, and get up quite freely to ask questions or to express their views on the problems under discussion.

The extent and growth of the Lagos Diocese south of the Niger will be seen from the following table:--

III. NORTHERN NIGERIA, although included in the Lagos Diocese is in every way a field apart. The conditions are so entirely different from those obtaining in Southern Nigeria, that it demands separate treatment here.

From the days of Graham Wilmot Brooke, Lokoja was the base for advance, and after Bishop Tugwell's party was compelled to fall back on Loko, Lokoja once more became the head-quarters with Loko as an advanced post. Then, in 1903, when Sir Frederick Lugard had overthrown the Fula power, Bishop Tugwell once more moved towards his goal, and succeeded in planting a station at Bida. Foothold was thus secured at two points north of the rivers. The situation might be compared to the strategic deployment of an army; with its base at Lokoja, where Niger and Benué meet; its right wing at Loko, a hundred miles up the Benué; and its left wing at Bida, 130 miles up the Niger. It was possible to advance on Hausaland from either point, should the way open.

In 1905 the opportunity presented itself; Dr. Miller, advancing from Loko, reached Zaria once more and obtained a foothold. The old emir had gone, but there were many people in Zaria, both Hausa and Fulani, who remembered Dr. Miller as a member of Bishop Tugwell's party, and his medical skill secured him a welcome. A small hospital and dispensary were opened within the walls of the city; but at first the people did not rush into them. Moslem suspicion and love of old ways are so great that the first patients "had to be sought in the by-ways and hedges, and won at a price." Dr. Miller himself pushed two of the first in-patients on his bicycle for seven miles. But love and medical skill triumphed; the hospital steadily won the confidence of the people; a boys' school was opened, and for sixteen years Zaria was the solitary mission base in Hausaland.

In the Hausa States a trouble of quite a new type has had to be faced. The British Government of the new protectorate of Northern Nigeria had made to both the Hausa peoples and their Fulani rulers a promise that there should be no interference with their religion, a promise both wise and just, and one that all true missionary workers would heartily endorse. Yet we firmly believe and stoutly maintain that a wisely-conducted evangelism is no breach of this promise, and that is just where government officials and the missionary leaders have not been able to see eye to eye. In all fairness, we must strive to see the government point of view. Knowing well the intolerant and inflammable temperament of Moslem peoples, it was only natural that they should desire to carry on, among the newly-conquered emirates, the good work of pacification and reform unhindered by an outbreak of Moslem fanaticism; and it is not difficult to understand that they feared that missionary effort might stir up bitterness and possibly lead to serious trouble. We may not agree with this attitude, but we are bound to recognize the difficulty the Government had to face.

Forbidden to advance into the Moslem emirates, the missionaries turned their eyes elsewhere. To the south, between Zaria and the rivers, a great pagan belt stretches across the Sudan, and in this the Government freely gave permission to work. About 1904 there was formed in Cambridge as a result of study bands organized by the Student Volunteer Missionary Union, the "Cambridge University Mission Party." Its members were eager to go to some hitherto untouched region.

The original idea was that some of the party should go out to Africa, while those members who remained at home supported them. But it was ultimately decided that they should affiliate with the C.M.S. The pagan belt of the Central Sudan was chosen as the field of their labours, and in 1907 they started a mission in what is known as the Bauchi Plateau, about 140 miles north-east of Loko. Two stations were opened, one at Panyam (in 1907) among the Sura tribe, and the other at Kabwir (in 1910) among the Angass. These two tribes were brave and independent spirited, but very primitive, both men and women being practically naked. The type of people may be gathered from the fact that when, in 1918, Bishop Oluwole went to conduct a confirmation among them, the twenty candidates appeared before him, the men entirely unclothed and the women with only a girdle of leaves, yet quite unconcerned thereby. For some years the C.M.S. had maintained a small staff of European and African workers in this mission, and not without success. But the financial strain in recent years, and the necessity for retrenchment, has led to the handing over the work on the Bauchi Plateau to the Sudan United Mission that has considerable work in adjacent areas. The S.U.M. is endeavouring to avoid any breach in the continuity of the work, and has staffed the mission with Anglican missiorfaries.

While the right wing of advance was being developed in the Bauchi Province, the left wing was also being strengthened around Bida in the Nupé Province. In 1909 a station was opened at Katcha, on a branch railway then being constructed from the Niger to Kano. Ten years later another station was opened at Kutigi; and in 1925 yet another at Kataeregi, still further up the railway. All these are in a country that up to thirty years ago was constantly devastated by slave raids carried out on a large scale by the Emirs of Bida and Kontagora.

The opening of the railway to Kano in 1912 materially altered the situation in the Hausa States. Around the railhead a small colony of Europeans sprang up, official, military, and commercial. The opening of the Kano emirate to trade also brought up the line large numbers of African traders, chiefly Yorubas, Ibos, Sierra Leonians, and Lagos people; and for these the Sabon Gari (or new town) came into existence, a quarter of a mile from the European reservation, no "foreigners" (African or European) being allowed to reside within the walls of Kano. Many of these African traders were Christians, connected with the C.M.S., and in course of time Government permitted an African clergyman to be stationed there to build a church in the Sabon Gari and minister to them. That was the first Christian foothold obtained in the Kano emirate, so long the goal of missionary effort. In 1924 a more substantial church was opened, and it serves for the different communities, united in their Christian faith but divided by language. The programme of the ordinary Sunday services is this:--

8.30. For Sierra Leonians (in English).

10.30. For Yorubas.

12.30. For Ibos.

2.0. Sunday school with classes in all three languages.

3.30. For Yorubas.

5.0. For Hausas.

6.30. For Sierra Leonians (in English).

This work is not really "missionary," but is rather with a view to ministering to the immigrant African Christians who live in the Sabon Gari.

The next forward step was taken soon after the close of the great European war. The C.M.S. applied for permission to open a book depot in the European reservation at Kano station. Government granted permission and gave an excellent site on the edge of the great open-air market on the "no man's land" between the reservation and the Sabon Gari. So in 1921 the book depot was opened, with the Rev. and Mrs. J. F. Cotton in charge and a Hausa Christian as head clerk. This man, whose father was one of the Emir of Zaria's councillors, had been converted in Dr. Miller's school at Zaria, and baptized by the name of David. As Hausas, David and his wife were able to secure a house in Kano city, and for some years were the only Christians known to be living within the walls.

The book depot soon proved a great success, selling books and stationery not only to people in the Sabon Gari and the European reservation but in ever-increasing quantities to Hausas. The Sabon Gari market, with its wonderful collection of booths and stalls of every description, and a strange medley of camels, donkeys, and load-oxen, was an excellent place for selling Christian literature, especially gospels, and people who came with the caravans took them back to their distant homes. No one was more anxious than Mr. Cotton to avoid anything that could provoke fanaticism. His mission was essentially one of friendship and goodwill, not of religious controversy, and he soon discovered that he was received as a friend by the Hausa people.

Hausa men, and even women and children, from the city came freely to the book depot to buy Hausa gospels and other literature, and to ask questions about Christianity. Some who were interested came readily to a little homely service held specially for them in a room on the compound, and later to a service for Hausas held on Sundays at the church. It was quite evident that several of them were turning their faces Christwards, and eventually they asked for baptism. On one memorable day, in a bathing pool just outside one of the city gates, in the presence of fully 2000 Moslems and others, Mr. Cotton baptized the first band of seven Hausa converts from Kano, men and women. The full baptismal service was used, and David and Dauda (another Hausa worker) preached clearly the message of Christ. There was absolutely no hostility of any kind manifest in that great crowd of listeners. Since then, other similar baptismal services have been held at the same spot. Regular services were held at the Court House for Europeans, until it should be possible to build a church for them.

At Zaria, where for so long Dr. Miller bravely held on alone, the work has developed. During the last few years younger men (one of them, and the wife of another, being doctors), and three women missionaries have joined the staff. In addition to the boys' school opened by Dr. Miller, a hostel for girls has done good service. All the C.M.S. work has been transferred to a new and more spacious site outside the town, and a hospital has been built.

With the development of work in Northern Nigeria, the Lagos Diocese was again becoming too large for effective oversight by Bishop Melville Jones and his African assistant, Bishop Oluwole. So in 1925, Archdeacon A. W. Smith, who for twenty-three years had been working in the diocese, was consecrated as assistant bishop, with special care of the work in Northern Nigeria. He resides at Ilorin, and travels widely over the great area for which he is responsible.

The prohibition of missionary work in the Moslem areas has never been removed. There has been no hostility on the part of the Moslems, but Government has always been afraid lest trouble may arise. We believe that there is no real ground for such fears, and that wisely-directed missionary efforts would strengthen rather than retard the interests that Government have at heart. Not a few of the highest officials are Christian men and more or less in sympathy with missionary effort, but there are a few who are distrustful or even avowedly antagonistic.

Having traced the expansion of the work during the last thirty years, we have now to think of the internal development of the African churches and their progress towards self-support and self-government, for no church can be deemed entirely satisfactory that does not learn to stand upon its own feet and to rely upon its own resources.

There is comparatively little poverty in West Africa, and hardly anything that can be called destitution. In this it differs from India or China, where literally millions of people live from year to year perpetually below the hunger line. Nature is bountiful to West Africa; the rains never fail completely, and famine is practically unknown. The very poorest villagers have food enough and to spare. Under normal conditions there is work for all, and all are able to provide for the simple needs of their families. The Nigerian people are born traders, the women as well as the men. Hundreds of thousands of women grow their produce on their farms (allotments, we should call them) and sell it at their own pitch or booth in the market. The coming of the white man with his commerce, his railways, his roads, and his motor transport, has stimulated trade, and large numbers of African villagers are busily developing their own native resources in a way they never thought of doing before. People who aforetime were content merely to provide for their actual needs, are now eagerly "making money." The policy of Government is not to give or sell land to white planters, but to encourage the Africans to develop it themselves and for their own benefit. The country has more than doubled its revenue in ten years.

All this means that the tribes and villages are self-supporting communities, and when they become Christians they are able to meet whatever cost their new worship entails. They always build their own churches, simple mud and thatch ones at first, and more durable ones later, when the increased number of Christians makes it possible to incur greater expense. Usually the Christian villagers pay their own catechist or teacher and maintain the school, and also take their collections in church for the maintenance of their simple worship. Formerly they made offerings to the old gods and spirits; now they bring love gifts and thankofferings to their new-found Lord. In the larger churches the expenses both of building and maintenance are necessarily greater, and as a rule the income increases proportionately, the congregation meet the salary of their African clergyman and whatever other expenses there may be, even though this may be difficult for them. In places like Lagos, Abeokuta, Bonny, Port Harcourt, and Onitsha, there are large churches, with big pipe orgSns and every accessory for worship, and sometimes even electric light; all these things are provided by the gifts of the African Christians, aided in some instances by gifts from special friends at home, but involving no cost to the missionary society.

It is the policy of the C.M.S. to pay the salaries, passages, and furlough allowances of its European missionaries, and provide for the building and upkeep of their houses; it also makes, where necessary, larger or smaller grants towards the cost of training institutions, hospitals, and other special agencies. Beyond this, the African churches are self-supporting. Nor is this all; most of the churches contribute also to central funds, and take up regular offerings for distinctly missionary work in their own or other lands. Great strides have also been made in the direction of self-government, for the policy is to train the Africans to bear the administrative as well as the financial burdens of their Church. The presence of two African assistant bishops and usually two African archdeacons, as well as over 100 African clergy (as compared with twenty-two European clergy) is evidence of this. Moreover, Lagos was the first diocese in West Africa to have a diocesan synod, and it is still more significant that upon it African clergy and laity very largely outnumber the Europeans. In 1930 a similar synod and church constitution was created in the Niger Diocese.

In such areas as Lagos, Abeokuta, Ibadan, Oshogbo-Oyo, Ilesha-Ife, and Ondo, the pastoral and evangelistic work is entirely in the hands of African clergy acting under district councils appointed for each area, a very remarkable experiment in devolution. White missionaries are more and more being set apart for purely institutional work, leaving the pastoral responsibilities to Africans. We have seen how, in the Niger Diocese, the Delta Pastorate has been autonomous for nearly forty years, and now district councils (similar to those in the Lagos Diocese) are to be found throughout the archdeaconry of Onitsha.