June 15, 1876.--Left Antananarivo at noon; many of our friends setting us on our way. Arrived at Ambohitrabily, where we slept in the Rova. It was very cold.

June 16.--A bitterly cold morning; did not get away till 8.15. Struck off from the main road, going north, so as to reach Amboromfotsy; halted for breakfast at 11, at a small village on a branch of the Betsiboka river, where the dirt compelled us to pitch our tent. Still bitterly cold; both the bracing air and the scenery continually brought dear old Dartmoor to my mind. Hamilton Moor was there exactly; went on till 4, when at the request of our men we turned aside west to a town called Ambatopisaorana, where we slept. A courier followed us from the capital, and gave me an opportunity of writing.

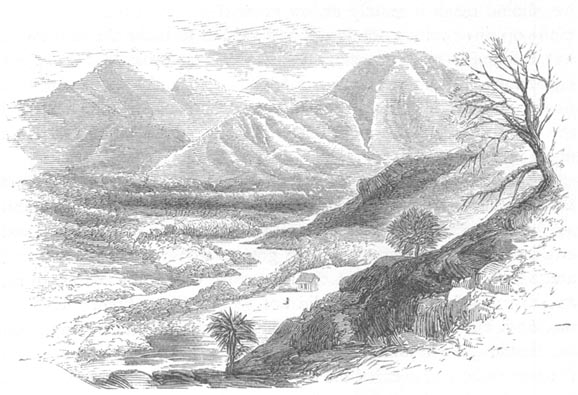

June 17.--Up at 6, off at 7.15; walked on for an hour to get warm. Crossed the shoulder of the mountain Ambato-be-tompo, our instruments gave us 5,300 ft. at our highest point. Crossed also the river Isara-Sahatra; breakfast at a small village Amparibe. Reached an important town in the evening, the name of which is Ambohitrankady. The people here were very cordial, and put us in a fine, large, but very airy, house. This place is most beautifully situated, being in fact a terrace on the top of a hill 4,600 ft. high, looking on the fine mountain Ambohihna to the N.N.E. which is a sort of boundary of the Sakalava in that direction.

June 18.--Got away at 7.30, crossed the river Mananara in a very frail lakana (canoe). It took us an hour to accomplish this, and the process was most amusing--a long ride--crossed another branch of the same river which we were able to ford; did not arrive at Amboromfotsy till 12.15, tired and hungry. After we had refreshed ourselves we held service in the nice little (native) church, after which we taught the people some hymns, and then held a long kabary with the people, promised to do our best for them, but this is a very difficult place to work. We are now approaching the Sakalava boundary to the west, as a proof of which, when we first appeared in the distance the people at Amboromfotsy took us for a party of marauding Sakalava.

June 19.--Got away at 8; followed a zig-zag course, E., N., W., N.E.; uncertain about our route, but met a native, the most genuine savage I have yet seen, who directed us. The people ran away from us when they saw us coming. Crossed a beautiful ridge 5,300 ft. high, and arrived for breakfast at a very dirty village called Mahatsara; pitched our tent, which was soon half filled with very dirty and very scantily clothed women, who wanted to be taught hymns, but lacked the necessary patience. There is a Hovah "church" here, but no teacher. I saw some rings on the fingers of the women, which made me suppose that they were married, but on inquiry we found they were all slaves, and that promiscuous concubinage was their rule. Left at 2, passing along the backbone of this district, the sources of the rivers were beneath us east and west, but I suspect they all find their way into the Betsiboka, though possibly those which flow to the east may join the Mahanoro. There is an important town named Betatao, to the south-west of Mahatsara. After crossing a fine hill we descended upon Androba, the northern limit of the Menakely of Ambohitrankady--a very dirty place, where we slept in an unfinished house.

June 20.--A very raw misty morning; got away at 7.30; saw a partridge (isipoy) and a quail (papelika); went through the forest which was very beautiful, but, as usual, apparently totally devoid of life. Through this forest (which is identical with that of Ankerimadinika, the eastern boundary of the great central plateau), we descended upon the plain of Tankay. The atmosphere became here sensibly warmer and I discarded my plaid. Crossed the river Maranibato, which flows into the lake Alaotra, and got to the first village of the Bezano-zano which is called Ambakiloha. Here we heard alarming reports of the small-pox in the neighbourhood of Ambatondrazaka. Got away at 2; a very close afternoon, which compelled me to banish my "Cardigan" went on till 4.15, when we arrived at a Tankay village called Analaroamaso, consisting of some fifteen houses, "one dirtier than another." Got into an unfinished and unoccupied house (which the people told us, with a grin, was the trano fiangonana) both of us rather tired, but a wash and dinner restored us. We are now 3,850 ft. above the sea.

June 21.--Off at 7.30; a detour necessary, to avoid the small-pox; worked eastward over cross roads, which were very bad for the feet of our bearers. Got to a very small village of five houses at 11. The people were very kind to us. Batchelor's boy Obela conducted a most amusing bargain for some sugar-cane. This place is called Antaimby. Off at 1.15, working north-east with a guide, when we came to a small village, the men waited for a change of guides and we took our guns and walked on--got some quail. Crossed the river Ambakireny and the hill Marivombona, 4,100 ft. Saw partridges--arrived at Andranokoboka, a town in the Menakely of Ambohitrabily belonging to Rajao Karivony, consisting of about five houses. all so dirty that we pitched our tent.

June 22.--Our route lay over undulating hills--road good. Crossed the river Ranofotsy, a curious sand-laden stream which must be very dangerous in the rainy season. It is the boundary between the Bezano-zano and the Antsianaka. After crossing this river we entered upon an entirely different country, which was apparently very rich, with abundance of large rice-producing swamps; got to a large village, Mangatana, for breakfast--put up at the Lafa, where we were soon the centre of an admiring crowd. This Menakely belongs to Andriantahiry, who is the adopted son of Rasoherina, the late queen, and it was administered, during his minority, by Rainizanoa. They brought us a child to doctor, but we were forced to decline. Walked on for some three miles, and then on over beautiful hills till, at five, we reached a small village on the edge of a swamp, called Andranomaria; pitched our tent on the edge of a swamp.

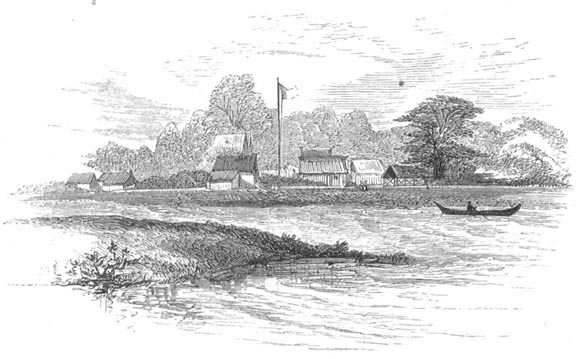

June 23.--Crossed the swamp, which was about two miles broad, and got into Ambatondrazaha in about three hours, arriving at 10. This town is about the size of Andevoranto (in 1875) but more compact. It stands on a slightly rising ground and is surrounded by rice-fields, which in the hot season must almost convert it into an island. It is evidently below the average of such towns, and this is due to the facility with which the people procure the necessaries of life. They just scratch the ground, throw in the rice, turn in their oxen and reap their harvest. Therefore they are more than commonly idle, and, as the natural consequence, more than commonly vicious. Mr. Pearse the L.M.S. Missionary, whose acquaintance we made last year at Fenoarivo, soon found us out, and gave us his school-room as sleeping quarters, insisting on our taking our meals with him, which we consented to do with the full purpose of leaving the town on the following day, but (Saturday, June 24) the Maromita rebelled and would not go, so we wished them good-bye and resigned ourselves.

Monday, June 26.--To our great delight the men reassembled and we got off at 9, reaching Ambohimanga for breakfast. Saw a great number and considerable variety of birds which were very wild. Got to Andriba, a very wretched village on the Lake Alaotra. The larger village was about two miles inland. Pitched our tent. We saw here, for the first time, the native mosquito curtain, which shows what a plague they must be here. A very good fish called fony, and the small duck called tabia, formed our dinner.

The next day, June 27, we continued our course along the Lake Alaotra. The birds were a continual source of amusement and excitement to us. We saw a magnificent white heron, and one of our men shot some birds. We passed by Ambatomanga and Ambohitava and breakfasted at Andranomena, a much cleaner place than our last halting-place. The people were not so degraded, though when B. asked them how they spent their time, they replied, "Well, we get drunk every day!" The master and mistress of the house were good specimens of their class. The woman was nicely dressed and had a silver chain with a dollar, and many coins and medals attached to it. After breakfast we turned off the lake to the north-east, and passing by a fine town, Sarovonenana, we arrived at Maherimandroso at 3.30. There is a Monday market in this town. It stands on a hill, and the view as you look back over the lake is very fine.

June 28.--The next day we made but a short journey to the ferry Andromba, where we crossed the river Maningoury, which is the great vent of the lake. We spent some time in duck-shooting, then had our breakfast and then went out again till 3. There were four varieties of duck and a wild goose called arosy. I killed two of these and got one; it is a magnificent bird with a white breast and back and wings a blue-black shot with green. The birds were very numerous and almost too tame; left Andriba Faharoa and got to Ambohitrevo just before dark. Here for the first time we found the mosquitoes troublesome out of doors in daylight. This is a large village much given to toaka. The people brought us no presents, but we received an intimation that if we had done as De L. did and given them toaka they would have brought us all manner of presents. One of the women who came to talk said that the Antsianaka had no souls, that they were just put into a bag and fastened up. John, our cook, who likes from time to time to come and have a gossip, told us this evening that there are professional men-stealers to be found, who will engage a man to convey entana for them, and when they have got him away they bind him and sell him. We heard of a worse case than this; a man married a girl, and when he got tired of her he changed his abode and sold her as a slave.

June 29.--Got away, attended by a large company of mosquitoes. We began to ascend from the level of the lake to the natural average level of the Tankay plain; we had risen nearly 1,000 ft. in two hours. The views of the lake as we looked back were very lovely. The highest point is called Efa Noizamfony because there all hope is lost of entering the Fony: this is 4,200 ft. Breakfast in the wild, reaching Amfalistrinyvola, a small wretched village, at 5. This was a hard day; pitched our tent.

Friday, June 30.--A cold morning, but soon found that I had fever. The cold fit was over before we got to Ambatobe. The people in this place, which is on the edge of the wilderness, seemed to be nice simple folk. The old lady in whose house we put up had evidently something in her house which she would not trust out of her sight, and she positively refused to turn out. We had rather an angry kabary, for the old lady being very much afraid we should rob her, adopted the tactics of pretending to be very angry at our being afraid of her. To show her that this was not the case we told her that the Vazaha were in the habit of bathing every day, and that we liked to do this in private. The old lady pointed to her mosquito curtain, and assured us that it would be all right, for that she would stay inside that till we had finished. Two slaves also slept in the room. In this place our men provided themselves with food for the wilderness.

On Saturday, July 1, we left the inhabited country and commenced our journey through the wilderness. Got off at 7.15 and went on for four hours; brought up at a beautiful spot for breakfast, where I managed to kill a brace of partridges. Our route lay for some time over very high ground, but we soon inclined to the east and got on to an undulating plain, which is the continuation of the great plain of Tankay, and follows the eastern escarpment of the great central plateau of Madagascar. After we came to the resting-place for the night we took a walk. The grass was in some places more than ten feet high. When we came back to camp, the men reported partridges, so I went out and got another. Our tent was not very comfortable. The men were not careful to pitch it on even ground.

July 2.--Went on four hours to-day, and halted for breakfast in another most lovely spot. In the afternoon rain came on, and when we arrived at our resting-place we were wet and wretched. We pitched our tent but the rain came through; poor Batchelor was very wet, and not only so but all his clothes had suffered more or less, so he had nothing dry to put on. This has been the first really trying day. Our route had lain through beautiful country, in which everything seemed to give the idea of the most perfect cultivation. It was impossible to resist the delusion that the mansion must be near, or the sort of dreamy surprise that there were no park palings; there was with all this the same wonderful absence of life. We are still at an altitude of 4,000 ft. Iron very abundant.

July 4.--In spite of the wretchedness of last night we both slept fairly well. We had made the mistake of pitching our tent near some trees which gave us no shelter and a running fire of drops. I was awakened by an unusual volley of these drops in the middle of the night and went out. The scene of the tent fires in the moonlight was most picturesque. We got off again to-day in drenching rain, which made the roads very slippery and difficult, but at 1 2 the sun came out a little and cheered us with its warmth, for the prospect of living continually in wet clothes had become rather depressing. Stopped for breakfast in another lovely spot where there was a little more life. We saw a partridge, two wild doves (domohina), and the large hawk (fahiaka); went on again till it was nearly dark, and crossed the river which runs to Ivongo, and which they call here Fandrarazana (this river disembogues to the north of Point Larée). Lit a large fire outside our tent and dried our things; here we fraternised with an old Sakalava Tsymandoa, whose tent adjoined our own. [One who pays for nothing on his journey, being a Government "runner."] We slept well, but both of us felt the miasma in the morning.

July 5.--This morning a hen partridge came to our tent; it was quite tame and we fed it with rice, and made it welcome; our route to-day was through forest; we saw new forms of ferns and orchids. Batchelor saw a flock of gidro or lemurs, I only heard them. Made our last halt in the wilderness for breakfast. Saw some quail, and heard akanga, heard also a peculiar noise which I believe to have been a wild boar whetting his tusks. [Apropos of wild boars, one of the Maromita told us a curious story of a fight between a wild boar and a crocodile. The boar was approaching some shallow water, and the crocodile drew near to seize him. The boar saw the crocodile, and accepted the battle, which was very furious. The boar ripped the stomach of the crocodile, but the latter succeeded in dragging him to deep water and drowning him. The dead bodies of both came to the surface and were secured by the natives, who preserved their heads.] After breakfast we crossed a ridge--a spur from the Ambiniviny range, from which we looked far away over the Sakalava country. It was a complete change of scenery, at once most beautiful and most refreshing. To the N.W. the Ambiniviny came to an abrupt ending, throwing out a most magnificent spur which looked like a lion bidding defiance to the Sakalava. and then bearing away to the W.N.W. This is quite one of the finest bits I have seen so far in the land. We went on about two miles beyond, and arrived at a Hovah fort called Maharitradrano on the river Amboaboa. Saw the bird which I have called a cormorant, but which seems to be the Vadimboay. ["Crocodile's wife," because he is not afraid of the crocodile and waits on him, probably feeding on some parasite.] We took up our abode in a tidy house, and when we had refreshed ourselves strolled down to the river, which is rapid and rocky; found a new water-plant called in Sakalava, Rondra, in Hovah, Tsilavandriana. Got back and had some talk with an old Sakalava, who is the Andriambaventy of the place. Presently we received a visit from the lieutenant-governor, with presents and excuses from the commander, who was sick. We were in a difficulty again. This evening the lady of the house would not leave, so we just had to put up with her presence.

June 6.--Batchelor took to the river for his bath; I was too lazy. We made a late start, for just as we were moving the commander sent for us and we had to go up and pay our respects before we started. We made a short run to breakfast, for Boto, Batchelor's pet boy, knocked up and had to be carried. Got our breakfast in a lovely spot again by the river side. This country bears distinct marks of volcanic action. The ground has been the scene of some grand convulsion, and the ranges of hills have the appearance of vast waves tipped with rocks. The mango trees were just coming into bloom here. The rivers seemed to run west, therefore we must, yesterday, have crossed a watershed, since the rivers of which I spoke appeared to rise in swamps, and run eastwards. [From lack of scientific observation it is almost impossible to define accurately our position. The Ambiniviny range ran yesterday almost due north, forming the western boundary of our route. Before we got out of the forest we crossed some very high ground, which I believe to have been a spur of this range thrown out to the west. The bend of these mountains to the N. N. W. makes a gap in the central plateau, through which we passed to Makaritradrano. This tallies with Grandidier's corrected map, and if I am correct, this spur must form the watershed.] We found it growing very hot, but it was cloudy, with a nice breeze. We followed the valley, which grew more and more beautiful, for some miles (the grass was in some places quite 15 ft. high), and then began to ascend a mountain-pass, bearing a little to the east. At the top of this pass we came to a magnificent view; a vast plain lay stretched out before us, bordered by fine, well-wooded hills, and terminated in the blue distance by a group of splendid mountains. I do not think I have ever seen finer scenery of the kind. Our men to-day rushed eagerly to the first tamarind tree (madilo) which we have seen. At the top of the pass we met a party of Arabs going up to the capital, and had some talk with them about our route, &c. Descended into the plain, which was all the more beautiful because the trees were beginning to put forth their spring foliage; there were some very fine ones which the natives called Rota. Got to a small Sakalava village, named Amparay. Here for the first time we saw the men engaged in making the native toaka, here we saw for the first time the Sakalava pigeons'-cote, which seems to be a regular institution among them. [I do not think it is fair to attribute all the drunkenness of the Malagasy to the Vazaha. Wherever you find the sugar-cane you are sure to find that men know how to make intoxicating drink. The native toaka is very like the spirit which the Devonians distil from the apple dregs and call "grammer's pins."] There was no house fit for us; pitched tent, and dined off the goose which the commander gave us at Maharitradrano. It was, I should think, as old as its donor--a fine bird but very tough. Poor B. succumbed, but I persevered. Mosquitoes very troublesome.

July 7.--An early start. Arrived at Mandritsara at 10. Crossed the river Mangarakaraka, and waited for the return of our messenger, sent to announce our arrival to the governor. [The Mangarakaraka rises in a very lofty range of mountains about 2 1/2 days ( = 50 miles) N. E. of Mandritsara. This range is called Mafaitantely. The Soufia also rises in the same range. These two rivers unite at the foot of Maranibato, which is the end of the Ambiniviny range about four miles west of Mandritsara. The Mairarano rises in the same range, and also the Tingumbala, which runs into Antongil bay.] We had just settled into a house when the commander and suite arrived. We went with them to the Rova and paid the visit of ceremony, and then went to the place which was allotted to us, a new brick house just built by an old Sakalava chief now Andriambaventy. We were the objects of very great curiosity. I suppose the people had rarely seen a white man before. They evidently thought from the amount of luggage which we had that we must be merchants, and were eager to buy or to get everything that we possessed. Made up our minds to pay oft our men and try to get a fresh team. Got some interesting notes of our route to Amorontsanga from a Sakalava who had travelled with Campbell. Then arrived a deputation with a bullock, a turkey, some fowls, and a bag of rice. Took a walk up the town, and saw our old Sakalava fellow-traveller, who greeted us very cordially.

Friday, July 7.--Breakfast late; our men were gorged with beef. Got a sketch and wrote letters. Luncheon. Letters. Prepared for our dinner at the Rova. This was, without exception, the roughest entertainment which I ever had the misery of undergoing. After it was over the commander conducted us home. B. and I took a walk to see the moon rise. On our return the servants came in for prayers; then our Sakalava friend came to see us, and had a most interesting conversation with B. It seems that our host was king of a large tract of land extending from the wilderness to the Soufia, his tribe is called Isimahety. They have never been conquered, but entered into treaty with the Hovah. This man has the privilege of even awaking the sovereign for an audience, so that the Hovah commander stands in wholesome dread of him.

July 8.--Did some drawing while B. held kabary with the men. After breakfast sent for the Mpitandrina of the Hovah church, who came with a considerable following. More work with the men, paid off all but fifteen. The church brought us presents. Then came our Sakalava friend, Iadana, and gave us much interesting geographical information; he is a most intelligent man and. I wish much he were going with us. Just as I was writing this we heard a great uproar, and that terrible cry which indicates that the Malagasy have some prey on foot. We ran out, and found two Makoa men fighting; presently one ran off", followed by a blood-thirsty rabble who declared that he was a thief. It seems that there had been some quarrel, and that the disappointed suitor in his rage snatched at the woman's lamba and ran off with it, probably not with intent to steal it. Be that as it may, he was hounded down and eventually his body was brought to our room--but he was only half dead, as well as half drunk, and we soon brought him to life again.

Sunday, July 9.--Held service here, Batchelor preaching to a large congregation. The people urged us very much to stay, and it is manifest that we might do as we would by them, though they are affiliated by letter with Ambatondrazaka. Went home with the commander and paid our respects, and were escorted back to our house by his suite. But there was no rest. First came ladana, and then a dear old lady and her flock to learn hymns. Taught them one. This is a most interesting place. I have never met with more encouragement anywhere, and from the fact that the old king of the Isimahety is here it is a most important place. It must be affiliated to Vohimare, since we heard afterwards there is a direct road about to be opened out to Isoaran Andriana.

Monday, July 10.--Arranged our luggage. The girls came for a final practice. General confusion and difficulty with the men; at last we arranged to give them $3 to Amorontsanga, upon which sore feet etc. disappeared like magic, and we started with all our old team. Wished good-bye and got away. Route N.N.W and N.W. After passing the foot of the volcano Be Molaka we wound up a mountain pass quite Swiss in character, with a fine rocky torrent rushing down. Saw two beautiful flowering shrubs, one carmine, something like a fuchsia. After we got to the head of the pass we descended into another plain; saw a flock of wild Guinea fowl (akanga). Breakfast at Putsapatsa, where we found one of the great men of Mandritsara, who had come to visit his sick wife. Continued our course N.W. across the plain; men tried to stop in a small village at 4, but I got them to go on till 5.30, when we found ourselves at the foot of Ambohimalaza, a grand flat-topped mountain, evidently an old volcano. The eastern side facing us was a sheer precipice of at least 1,000 feet; saw a great number of the large bat which is called the Fanihy, sometimes the flying fox. Saw also the wild goose, &c.

July 11.--Continued our route, crossed the Ambohimalaza range by a pass. The route was very lovely, similar in character to the one I have described after leaving Mandritsara, but who shall describe the view from the summit? We looked right away north-west till we lost ourselves in the maze of mountain, and plain, and river; we thought we saw the Mozambique, but I could not be quite positive of this. The forms of the mountains were very beautiful; descended the mountain side in a storm of wind and rain. (N.B.) This is the western escarpment of the great central plateau. The country was well wooded and well watered, but the same absence of life prevailed till we got to the lakes and the plain. Here we found immediately wild fowl of all sorts, in fact, almost all the birds which we saw at Lac Alaotra. We stopped for breakfast at Salohy, where letters from the capital overtook us, which were a great refreshment. On to Amoron-Soufia, a lovely spot, situated, as it name indicates, on the banks of the river. Pitched our tent. Letters. Mosquitoes and toothache kept sleep from me.

|

|

|

July 12.--Despatched letters. Started across the river which is about half-a-mile broad, but very shallow. The men begged me to take off my hat. They have a pantheistic idea that Zanahary, the Deity, dwells in the grand features of nature. I complied, and when we had crossed I thanked God for bringing us safely across, which seemed to afford them much satisfaction. On through well-wooded country, but by a very difficult route. We had evidently missed our road to a village called Ambohimitrinza, working W.N.W. for nine hours. Batchelor did not follow me; got breakfast and waited till 4 p.m., when on consulting John he casually remarked that there was another road to the east. I was in my filanzana directly in the vain hope of reaching Befandriana that night, but we went on till it was dark and then were fain to put up at a small town called Marolampy. Teeth troublesome all day, but poor B. has no bed and no creature comforts; I am very sorry for him. Toothache and mosquitoes again. Up at cock-crow.

July 13.--Got away as soon as we could see; went on through two or three small villages, one of which seemed to be en fÍte. We heard that there had been a wedding there that morning. Arrived at Befandriana at 10. Alas! no Batchelor! despatched a messenger in search of him. The town seemed to be rather in an excited state. I was put with all my luggage into the house of the Andriambaventy, who was busily engaged in selling rum to the natives. I was presently summoned to see the arrival of a large party of Sakalava, who had come on a fanompoana to repair the river. It was a most striking and interesting sight. These men looked very wild; they had been called out from the remote parts of their district; they are all of the tribe Behisotra. We were told that it is the intention of the government to make this a large town. Of course the house was soon crowded as successive visitors came to stare at the Vazaha and examine his luggage. Got a sketch of the kabary which they held. Breakfast; after which to my great delight Batchelor arrived. He had missed his way, misled by the sound of a shot which he thought must have been mine. Much kabary, &c. We were most respectfully treated by the commander. The district of these Behisotra extends from the Soufia to the Maivarano, and as the place was so full it appeared to us at first that we ought to spend Sunday among them, which they pressed us very much to do. Batchelor soon had his hands full, the ladies being very anxious to learn to write.

July 14.--A bad night from toothache, and a slight attack of dysentery. Took rather a long stroll to a pool, where we saw many wild fowl. Got back to breakfast, after which I rested while Batchelor talked to the people, and taught them a hymn-tune.

After dinner we had more singing, but rum-drinking was going on to a frightful extent, and we became aware we ought not to be in a house where there were so many people. I had to turn one man who was behaving ill, bodily out, and we had almost to compel the others to go. The women warned us that we were in danger. These Sakalava are a wild, lawless race, very handy with their spears, and the Hovah have no real authority over them; but they, on the other hand, have no nationality in them, and therefore never can be more than a tribe, and will inevitably die out before civilization in whatever form it may come to them. As it is, rum is doing its fatal work. Their religion seems to be belief in Zanahary--the Supreme Being, to whom they make vows and offer sacrifices. He dwells, they say, on the mountain tops, and in the forests, and rivers, and with Him they reverence and offer prayers to the souls of their Razana. I believe the people would receive a Vazaha well if he had the tact requisite for their management, but they are very wild and fully armed. The women are not so good-looking as the men, but some of them are pleasing in appearance. They wear abundance of silver chains and dollars, and other coins as necklaces.

July 15.--We had but little sleep. The people seemed to be all drunk, and our own men were especially noisy and troublesome. B. had to turn out twice to disperse them, moreover, there was a man in our house who kept up a lively conversation all night. Taking all things into account, we made up our minds not to remain. We, therefore, paid a visit to the commander, who presented us with a dollar, and came to see us off. We had a row at starting, which I left Batchelor to quell. Started with a guide, and went on for three hours, stopping for breakfast at a small village named Maromandia, where we made acquaintance with an old man, a Betsimisaraka, who is a relation of the commander at Befandriana. It would seem that the Betsimisaraka impinge upon the Sakalava and mix with them in this district. Followed a N.N.W. course over a well-wooded undulating plain, bounded on either side by mountains, those to the east evidently volcanic. Saw many parrots. Got to a small group of huts, where we pitched our tent and rested, thankful to be safely out of the den of iniquity which we had left behind us at Befandriana.

July 16.--Continued our course with some uncertainty; came to a pond where I saw my first crocodiles, but not very near; saw also a very beautiful bird which I think must be a variety of the Tactso. They called it Tako daro, it was dove-coloured and blue, with beautiful bird's-eye marks on the tail. Saw also the bird which they call Mananhara, also Vadimpory, perched on a tree which indicates that it is not web-footed. Got our breakfast in the wild; general course N.W. Stopped at 4.15, on the bank of a stream, and pitched our tent.

July 17.--A very hot morning, but at 9 a fine breeze sprang up, which made it more endurable. Went on over a plain, up and down small hills, and stopped for breakfast on the banks of a rocky stream with plenty of shade: a most enchanting scene, which was enlivened by the arrival of a large party from Amorontsanga, who were bringing up the bones of the governor who died there last year. It was very hot this afternoon. Went on till 3.30, when we made our halt on the banks of a well-wooded rocky river named Aronda, which reminded me very much of the Tees at Rokeby. It wears its rapid way through rocks of gneiss, and is very sparkling and beautiful, with fine overhanging trees and steep banks on either side. Batchelor says that he saw the sea to-day. We shall, I hope, be on its shores the day after to-morrow. We crossed the river Atsingo, a fine rushing stream, with a rocky bed, which, in the rainy season, cannot be crossed, either by fording or by lakana; in fact, this route must be perfectly impracticable, except during the dry season.

July 18.--Made more westing to-day to fetch the base of some hills which we had to circumvent. Went through some fine forest; missed our way, and eventually stopped for breakfast at a village in the district of Betainomby; found that it was occupied by a Betsimisaraka, a slave of Rainimaharavo, who had the charge of his cattle in this district. Missed our way again; it is most difficult to keep the track the bullock paths are so numerous, and so much trodden. Mounted a hill and went along the ridge for some distance, at length descended into the plain which we followed for some time, and eventually mounted another hill which brought us to Maivarano. The mosquitoes were very bad here. I have now been travelling for two days without an umbrella, and am thankful to say I am none the worse. This is the worst night I have had; sleep was quite impossible.

July 19.--Got down early to the river; a fine, wide, meandering stream. Saw again the very fine white bird called Voron'osy, which I saw first on crossing the Aronda. The timber on the banks of this river is the finest I have as yet seen in Madagascar. Got on to breakfast in a small Betsimisaraka village. It was intensely hot this afternoon. I saw in this place a child playing with a bow and arrows, which was rather curious, since, so far as I have observed or heard, the use of these weapons is unknown in this country. It was just such a bow as a boy would make in England. I got rather a severe fall from my filanzana to-day, and this afternoon it was impossible to keep awake, Halted for that day at another small Betsimisaraka village in which, however, there were many Sakalava. Two young Sakalava came and talked to us for some time. They said that their tribe was subject to the Hovah, and spoke of their Fanompoana, or state service, without the usual expressions of dislike. They gave us the name of their tribe Tandrona, and told us that north of Amorontsanga we should find the Antankara.

They said that there was sandal wood in their forests, which was not used for merchandise but by themselves for scent. They were delighted at a present of a box of matches, and immediately got a piece of sugar cane and broke it in half, giving us one piece to eat in token of friendship. They told us that the Fossa was plentiful in the forest, and that they ate its flesh; that it was fierce and would sometimes attack men. They were very amusing and very curious. They were quite delighted when we showed them some white sugar and made them taste it, and carried off some to eat with their rice.

July 20.--Our route lay over the same beautifully wooded country, and at last we caught a real view of the Mozambique Channel, which was a feast for sore eyes. Got to a village named Ankerina for breakfast. This was a great sugar and toaka place. The people were all more or less tipsy. Followed the course of the river Malaza for some time; at our last crossing the water was over the men's hips. Ascended the hill to the town Andrano Malaza, where we determined to sleep. The tide soon came up, and we went down and inspected an Arab dhow which had just come in with a cargo of spirit to fetch rice. Tried to get a cast to Amorontsanga in her tomorrow, but it could not be arranged. We had a nice talk with a Hovah, who came to see us and who is living here. He told us a good deal about Amorontsanga. Curiously enough, one of our bearers, a Makoa or Mozambique slave, found to-day at Ankerina some of his own people, not persons whom he had known but who turned out to have been brought over from his tribe in Africa. Of course they were slaves. This led to some talk about the condition of these people. It seems that among the Makoa they have no domestic slavery, but when they go to war the captives are sold to the Arabs generally; but if one of the captors takes a prisoner to his own house it not unfrequently happens that he marries the daughter. We calculated that two-thirds of the population of this district were Africans. There are here Betsimisaraka, Antsianaka, and Sakalava living together, with the ubiquitous Hovah in full force. I should say that the Sakalava and the Arab are the chief traffickers in the slave trade. Batchelor overheard a Makoa describing an elephant to his companions. He said that it was so big that eight men could lie down on one of its ears. We are also told that a horse 7 fathoms (42 feet long) had been brought over by the Arabs and was now at Nosibé.

July 21.--Started on foot this morning and walked on for an hour, and soon came in sight of the bay. There were several islands. The sea was perfectly calm, and it was intensely hot. There are many lagoons running up from the sea, which form perfect lurking places for pirates or slavers. Saw some beautiful flowering shrubs. Went on till four and rested at Ambaliha, where we found a tidy Hovah church, which is affiliated by letter to Ambatondrazaka. This district seems to be in the hands of a slave of Rainimaharavo, who ran away and was not heard of for many years, during which time he contrived to amass considerable wealth. The native catechist, who came to see us, seems a very good man.

|

|

|

July 22.--To-day we hope to arrive at Amorontsanga. The first part of our route lay up a very steep ascent, and was very beautiful. Saw the Righi Spectre. My filanzana broke down, and I had to walk a good deal. When we got to the top of the hill we had splendid views of the sea; saw again the Takodaro; got to Bezavona to breakfast, where we found the Betsimisaraka element predominating. The people here were very suspicious, and wanted to stop us, but we were firm and they gave way. Arrived at Amorontsanga very tired. It is a strange place, full of bastard Arabs and men from Kutch, near Bombay. The Arab dress distinctly predominates. A man, who had rascal strongly written on his face, took us under his protection and brought us to his brother's house. Such a place! The house was built of stone, there were no windows and no ventilation; it was like going into a foul oven. Sleep in such a place was quite impossible, so I swung my hammock in the verandah, and Batchelor put his stretcher on the other side, and so we managed to get a delicious night's rest.

July 23.--This being Sunday we got our bearers together and started for the battery, which is on the top of a hill about two miles inland. The governor, Rainimiraony, seemed to be a good, kind man; his son Festus had been a pupil of Mr. Richardson's at the capital. Had service with them; Batchelor preached and I gave the blessing. The singing was not so tedious as usual. After prayer we had coffee, eggs, and conversation in the governor's verandah, where the breeze was delicious. In the afternoon we went to the "church" in the lower town. The congregation was not large, but outside were a large number of Mohammedans, who came to hear what we had to say. The Arabs are virtually masters of the coast. Their policy is very subtle. Outwardly they cringe to the Hovah, but in their hearts they dislike them. Their motto is "The husband of my mother is my father," which simply means, I acquiesce in the government of the land in which my lot is cast. They are on the best terms with the Sakalava. They dislike the French and fear the English. Ali Mahomet Sambarava volunteered the statement that only bad Arabs were slavers, that he and such as he (!) did their best to put it down. An Arab will not marry one of a different religion unless she be a queen or an heiress, nor will an Arab woman marry one of a different creed, probably with the same exceptions in favour of wealth and rank. They abstain from wine, &c., professedly, but the captain of our dhow enjoyed it much. By profession they have only one wife, but Breda had three. When we told him how wrong it was, according to his creed, to have more than one wife, he put on the most absurdly penitent face and said, "Oh, I know it, and I pray earnestly to Mohammed that I may resist the temptation of taking a fourth." Abdullah, the mate, was a higher stamp of man altogether, a fine, handsome man of the true Caucasian type. The Arabs are just as free with the Sakalava as they are with the Hovah, and use both with characteristic cunning as it suits their purpose, playing them off one against the other. Went to see the Mpitandrina, who was sick. The people escorted us home. Took a walk with Sambarava to a very fine cocoa-nut grove, in which the shade was perfect. The light of the setting sun was most gorgeous, I have never seen such colouring in nature before. This is a most remarkable place, quite as important as Tamatave, but with this difference, that here you have no Europeans. The Arabs and Kutch men are the traders. There are also many Suahili from Zanzibar. There is also a large number of Mozambiques, and there can be no doubt it is a great centre of the slave trade; no large vessel can come in. The bay has many islands, which afford every facility for the traffic. The Arab dhow is built for swift sailing, combined with the maximum of accommodation, broad in the stern and very sharp in the bow. It seems passing strange that we should only by chance have heard of this place, and yet I have seen none of greater interest, nor one in which there is a finer field for a missionary. There are here two mosques and six imams. The people crave a teacher. We were told of another town, Ambohimadilo, opposite Nosibé almost as large. Our friend, Sambarava, is a rare specimen; his mother was an Arab, his father a Comoro man--happy combination! He has a smattering of many tongues, is, I opine, a fair specimen of the bastard Arab, who acts as interpreter to our cruisers. The bays on this coast are very shallow, and I suspect are filling up rapidly. The rivers bring down their volume of silt without any hindrance, and the honko tree, which seems to rejoice in the brackish water, helps the process. [Identical with the mangrove.] This tree is propagated in a curious way, it throws off young plants much in the same sort of way as the asplenium bulbiferum. The bulb or nodule is weighted so as to make it fall straight, and the young tree starts at once. The tree is small, but the wood is extremely hard, and the bark affords a valuable orange dye. There seem to be a great many Sakalava women in this place. Dismissed our maromita and engaged a dhow. Had a good deal of talk with the Arabs, and was confirmed in what I have always heard of them, that they are most unmitigated rascals; nevertheless I am bound to say they were very kind to us, and they never fail in politeness. Our host, Mohammed Ali, is a very pleasant and intelligent fellow.

Tuesday.--Got a most refreshing bathe. When we returned dressing was a difficulty, for our Arab friends came to greet us.

Wednesday, July 26.--Got a bathe. A visit from the governor announced; we gave him some wine, and then we walked about with him, and eventually sat down under a new dhow and devoured some akondro. Gave the commander a new knife, after which he made us sundry presents, gave me a dollar, and said Veloma; packed our entana, and went on board the dhow at sundown.

Thursday, July 27.--Got up and shook myself, washing impossible. John and Mark in the depths of woe. We had not made much progress during the night, but are now slipping along with a fine breeze from the south-east. The situation on board is amusing and interesting. Bow, the Arab boy, sits by my side chewing sugar-cane, in which interesting occupation he has succeeded in engaging me. Batchelor sits opposite, having just completed his journal, and tries to draw us. Our servants are asleep, poor victims, bewailing no doubt the day that induced them to venture on board. What I should have done if I had been as bad as I was yesterday I cannot say; happily I am all right. Rounded the point Antanghena at 10, course N.E.; opened a fine bay with three islands off the north headland; passed the river Kakamba, giving the name to the district, with a town of the same name at its mouth; sighted Nosibé at 10.15; rounded the point Kidronga at 11.30--in the bight of this bay is Ambavatovy, where coal is found, and more inland another large town called Amboahangy. The view of Nosibé, as we approached, was very fine. As we drew nearer the sugar plantations became visible, and the house of Messrs. Oswald and Co., the German merchants. The island called Kioba lies to the east of Nosibé, separated by a narrow strait; it is subject to a Sakalava king in alliance with the Hovah. The mountains on the mainland are very fine, one peak especially runs up into the clouds, and I should say was from 8,000 to 9,000 feet high. Landed at Nosibé at 4 o'clock and went to the house of Messrs. Gallard and Zumpff (Oswald and Co.), who received us very kindly; dined and slept there.

Friday, July 28.--Went across the bay to look for the Norwegian, Mr. Hankervinck; not finding him, went on to Helville, the French town. The scenery here is very beautiful. There are good roads and houses, and I actually saw a donkey-cart; but it is in truth a wretched place. Externally, Nosibé is a lovely spot, but it is extremely unhealthy. The people seem half asleep, and from 10.30 till 2 the shops are shut and all business suspended. The difficulty of labour is very great. The Jesuits have two fathers and several brothers and sisters here. This might be the centre of a strong R. C. Mission; but the French, as they make bad colonizers, make also, with all their self-devotion, indifferent missionaries. They do little outside Nosibé except through their school, and in the various islands, as well as on the mainland, the ground is free for us, and must be worked from the east coast. There is almost no trade, and the people complain that their country has forgotten them. Went to the Indian town to look for our friend, and not finding him, returned and found him waiting for us. He is a very nice, simple fellow, a trader, and is a missionary, i.e., in the sense of always trying to do good. He told us of a very great peril from which he had lately escaped: he was driven across the Mozambique in a canoe, with no provisions and no water, and was six days without food; at the end of that time he was dashed on shore and seized by the natives, who stripped him of everything but his trousers. He was quite starving, and seeing one of them with a yam begged for it. The man pointed to his trousers, and made him understand that he must buy his food with them: but Hankervinck said, "No; I know I must die, and I had rather die in my trousers."

July 29.--We had to make a fresh arrangement with the captain of the dhow, which was effected by our German friends telling him that if he gave us any more trouble his rudder would be unshipped and locked up in their store. One of the frères came over and I was introduced to him. He was a pleasant, simple man; he spoke only French. Got my filanzana mended partly by the German blacksmith, partly by an Arab. Watched the Sakalava bringing in the rubber. After dinner wished our friends good-bye, and got on board at 1.45. A fine breeze. Rattled away between the islands Kioba and Nosibé, passing Tafondro, where the old L.M.S. missionary, Johns, was buried. Got to Tafia Amboty, the principal town of Nosipaly, at 4.15; this is the residence of the Sakalava king, Isi Manoloka, who sent out a lakana for us. We found him seated on a log of wood on the beach with his chief people about him. He is a pleasant-looking young man, with a good expression of face, not as yet marred by toaka. He wore the Arab dress. He made us welcome and talked a great deal about Imerina, about religion, and about the slave trade. As to the latter, he did not seem to understand the action of England, but he seemed quite to take in Batchelor's argument that the position of the English made them the protectors of the weak, and that it was their duty as a nation to take care of the oppressed; and he allowed that it would make him very unhappy if his children, and his wife, and his friends were carried off and made slaves. He gave us a small, but clean and tidy, house, in which we were glad to seek repose. Batchelor was suffering from fever. This is a lovely spot, the formation of the land apparently converts the sea into a beautiful lake. The mainland is about a mile from the island. The sight of the setting sun on the mountains was most lovely. We watched a herd of cattle swimming across from their pasture on the mainland with their attendants. The fire-flies were very delightful, and the flying foxes seemed to abound. We have to remain here until the sea-breeze to-morrow. We got to sleep very tired, but were awakened at 1.30 A.M. by some loud talking outside our house, and before we quite knew where we were, our door was forced open and three Sakalava, fully armed, made their appearance and sat down near my bed. I put away my watch and knife, and struck a light. It was just one of those occasions when one could not tell what was coming. However, Batchelor talked to them and told them who we were, and that the king had given us the house. It seemed that the leader of the band was the tompo (master) of the house, and having returned unexpectedly from Nosibé, was naturally surprised to find it occupied. It was quite impossible to say what they might take it into their heads to do, and the scene was not a little curious. However (D.G.) they retired peaceably and left us to repose.

July 30.--The king brought us his child, who has a well-developed fifth finger hanging from the little finger of the right hand. Prayers. Got away at 1.45; a lovely sail across a large bay; got on a sandbank at 6 P.M.; floated off with the rising tide and got into the river, where we stuck again at 2 A.M. When it dawned we found ourselves in a very curious position. The river, about a quarter of a mile wide, bordered by forest; and ourselves high and dry. The men caught crabs and fish. Beautiful birds about, herons, the white ibis, and curlews.

July 31.--It was very chilly till the sun rose. After a painful waiting, put off at 10.30, fondly deeming that we were going straight to Ifasi; but alas, we went up the river till the trees stopped us, and finding we were wrong, backed out. This process we repeated three times, our pilot evidently knowing nothing of the route. It seemed very likely that we should have to pass another night in a most unwholesome atmosphere, and moreover, we had no food on board except rice; but we did our best to stir up the men, and happily they began to sing, very feebly at first but more strongly by degrees. Happily, we did not stick fast, and got safely to the mouth of the river; there we espied another mouth, in which there was a dhow, for which we made. The captain told us that the name of the river was Anton, that we were not right for Ifasi, which, except in the rainy season, or at the highest tides, cannot be reached by water; that we were close to a town called Anjiamangirana, and he sent his lakana to summon the king, who duly arrived and made us welcome. We slept on board, and in the morning (August 1) landed and made our way through the mangrove swamp to the town, which consists of a few houses in a clearing, surrounded on all sides by bush and mangrove, and perfectly concealed. The malaria is very strong here and the mosquitoes abominable. Batchelor with fever again. The people were very kind to us.

August 2.--Batchelor better (D.G.) Tried to get Mpilanza to take us to Ifasi; only got four, so Batchelor has to go alone, for which I am very sorry; but there is no help for it. He stood the journey better than I expected, it does not seem to have been more than about six miles. The people all seem to have been more or less drunk. The king held a kabary and read the letter from the Governor of Amorontsanga, and after some palaver, twenty-five men were promised for Friday at five dollars a man, at which rate our journey to Vohimare from here, which is about five days' work, will cost us more than the journey from Mandritsara to Amorontsanga. The king at Ifasi has been to Bourbon and speaks French fluently, another proof of the strength of French influence on the west coast north and east of Nosibé. Isimola, our king, came and chatted with us for some time, and told us all about M. Lambert and the French pseudo-treaty. The land which he wanted to get was around Ambavatovy, where there is coal, iron, and copper, and almost certainly gold. The Hovah will not allow a Vazaha boat to land there now. We watched to-day the process of baking pottery. I bought a water-bottle which a girl was shaping with her hands. They kindled a wood fire on the ground, and threw in a quantity of rice chaff, which gave it a fine black colour.

August 3.--We had a good deal of talk to-day with Isani, the Arab captain of the dhow, and decided to accept his offer to take us to Nosi Mitsiou, from which he told us we should have no difficulty at all in making our way to Antomboka; of this I am very glad. It will cost us less, and we shall have an opportunity of seeing thoroughly the northern part of the island. Got a sketch, and packed my boxes. Took a walk with Batchelor through the mangrove swamp, in which there was nothing especial to observe except the exceedingly luxurious quality of the soil and the abundance of salt which lay on the ground like hoar frost when the tide retired. Much amused at, the antics of a native, who imitated the various ways in which the different people fight. The mosquitoes were, if possible, worse than ever; when the tide began to flow, and the breeze came in with it, we heard a noise like the singing of a kettle, which increased till we were led to investigate what it could be, and we found that it arose from a swarm of these wretches, which had taken possession of our dwelling. I was fairly stopped from writing by them. We both feel that it is time we were out of this place; it is most unhealthy, and there is positively nothing to do, so far as one may say so, and nothing to see.

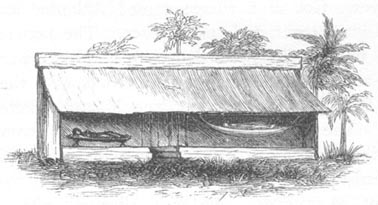

August 4.--This morning a lakampiara arrived from Nosi Mitsiou with a messenger from Ratsimiaro going to Ifasi. [So called from its having a raised platform in the middle, which lifts the sitters from the floor of the lakana.] This messenger was a fine old man, with white, closely-clipped hair, attended by several men, two of whom carried spears, and three muskets, the old Brown Bess, with the Tower mark--in beautiful order. I have seen none such among the Hovah. The lock of one which I handled was perfect, and the whole train would have done credit to an English soldier. We heard a good deal to-day of the old story about Radama II. being still alive; I suspect this is the cry got up by the Extreme Left at the capital. The lines of these lakampiara are very beautiful. Alas! we have to linger on here till the evening and sleep on board. Prepared our luggage, and got away before dark. As we went away I again examined the approach to the town. I can conceive nothing more easy than for a dhow to run a cargo into this river, and distribute it through Ifasi, and that this is constantly done I have no doubt. Made our beds on deck, and weighed anchor at 4 A.M., August 5. Light breeze from the east till 10, when it fell; dead calm till 12. We first saw the wind coming, and full half an hour before it came up we heard it. "Miresaka izy" (it talks) was the cry; it came from the north-east, so we had to go along close hauled. We anchored at Nosi Mitsiou at 2.30, but there was a heavy wash on. After some time, a lakana came out, having on board the eldest son of the king, Isialanana, and his brother, Mamba, two fine young men, the eldest rather of the "Buffalo" type. Their suite came with them, all fine, bold fellows. After hearing who we were, and greeting us very kindly, they returned to tell their father all about it. Nosi Mitsiou is an island of considerable size, very long and narrow. The king is allied to the Hovah, and pays a small poll-tax to them. The French commander often visits them and pays them thirty dollars per month. At one time there was a French priest or frère in residence; he has left but the children, who receive any education at all, are sent to Nosibé. It would therefore appear that there is a sort of provision for Christian teaching; but I must make this statement with reservation; we shall not get at the whole truth directly. We did not get on shore till near sundown, weary of waiting, and it was a service of some danger--there was a heavy wash on. I can quite understand, from the experience of to-day, how it came to pass that the Norwegians were blown across the Mozambique. I suppose that, just at this time, between the end of the south-east and the beginning of the north-east monsoons, the weather is generally more or less unsettled. Got a message that the king will receive us to-morrow; meanwhile, he provided us with a spacious apartment, with the unwonted luxuries of bedsteads, table, and chairs, and we got a sound night's rest, for which we were very thankful.

August 6.--Got a swim; but alas! no clean things, nor toothbrush, nor sponge, nor nothing, not even a towel. Started from this town, which is called Antsakoa, for the king's town, which is called Fasandava, about a mile and a half. We were met by Alidy, the king's brother, who conducted us into the royal presence. On entering the room, which was long and narrow, we found his majesty, attired in the black embroidered Arab kapota, seated in a chair of state, at the end of the room, with his great people about him. We made the usual kabary, and gathered that he was perhaps more inclined to the French than to the English, because the English had helped Radama to get his land from him; that he was very anxious that his people should be taught, more, perhaps, that they might be able to make soap and gunpowder than for any other reason. Still, there would be a fair opening here for a Mission if a man could be found who could turn his hand to these things. This king was formerly ruler over all the land north of a line drawn from Nosibé to Angontsay. After our audience the king sent us food--mutton, rice, and milk--after which we were summoned to another kabary, and told him all the news. He sent for us again a third time, and in the evening we paid him what we hoped was our farewell visit. In the afternoon he showed us our Union Jack, which had been presented to him by the captain of a ship, and a document from a certain Raymond O'Connor, whom he had appointed generalissimo of his forces, and to whom he covenanted to cede Nosi Mitsiou to the English when he should have been put in possession by them of his ancient territory; this man appears to have been murdered shortly after by the Sakalava of Menabe. We gave the old king a present of thirty dollars, and to Isimolu for his good will ten dollars. We had also covenanted to give Atani twenty-five dollars, and for this we were to be franked as far as Antomboka. Tried hard to get to sleep, but the fleas were too many for me, and after tossing about for three hours, got up and swung my hammock.

August 7.--Got a swim. After breakfast a farewell visit to the king, and after much talking, got on board the dhow; but the captain had, with characteristic indolence, lingered till the land-breeze was over, and we were almost stationary till 2, when the sea-breeze came up. The island looked very lovely as we left it. We stood right across the bay, passing Nosilava on the left or western side; but it was not a comfortable trip, we had too many (twenty-five) on board. We breakfasted off goat liver and kidneys, lunched off a leg of goat, dined oft" hashed goat. I had had some curiosity to taste goat's flesh, and it was fully gratified; I have no desire to taste it again. The breeze fell light as the sun went down, and it was dark before we made Nosibony, where we anchored and lay down on deck in our clothes for a night's rest.

August 8.--A fine breeze brought us speedily to Antafiambe, where we anchored and landed on a beautiful spot, and after a time were duly introduced to the king, Derimany, cousin of Ratsimiaro. The interview took place under a grand old tamarind tree, and the scene was most picturesque; the Arab dresses, with their red caps contrasting with the dark skins, and white lambas, with abundant silver ornaments. Of the Sakalava we were told that the people were beginning to come back to the mainland, and were settling in small towns on the coast; that the king would gladly receive a teacher, and would send him his own children. Our going to Nosi Mitsiou and coming on here has given us a much deeper insight into the habits of these people than we could possibly have obtained in any other way. This part of the coast is more manifestly volcanic than anything that I have seen, except Trinidad. The lava must have flowed right down into the sea. Took a walk into the bush, where I saw my first lemur, a beautiful creature, who looked curiously at us with its large lustrous eyes. When I came back I was asked to prescribe for a man who was very ill; I begged them to wait until Batchelor came, but the poor wretch died almost immediately. He had bought a barrel of rum, and drank it incessantly till it killed him.

August 9.--Got a swim, then a visit from our conductor, Alidy. Then we heard guns, which announced that the funeral festivities had commenced. The dead man was a Mohammedan, but they do not give up the burial customs of their fathers on this account. Paid a visit to Derimany, as is usual on these occasions. Talked to him for some time, and inspected his armoury; his guns were antiquated, but all in first-rate order. We heard some of their customs as to the punishment of crime. If a man kills another wilfully, he is put to death; if by accident (kajiry), he pays twenty dollars to the dead man's representatives. In one case a man set a trap for a wild boar in the road, which is forbidden; a man fell into it and was killed. Ratsimiaro ordered all the property of the offender to be given to the family of the victim. Went to the kraal to inspect a bullock which was to be killed for us. All this time beef and rum were continually being consumed, so that all the people were more or less the worse for liquor except the strict Mohammedans, who do not touch it. One man came in and seated himself at the foot of Batchelor's bed, and stayed till we were forced to turn him out.

August 10.--My fifty-second birthday. Alidy paid us an early visit, and Derimany brought a friend to see us. A good deal of political talk. I am afraid we are here till Saturday, this unfortunate burial upsets everything. Took a walk; saw some curious fruits and the bird which I have called takodaro, but which the Sakalava here call birao. They also call the parrot quera, evidently a Portuguese name. Got a sketch of the opposite island, "Antalyn." A long talk with Alidy and others. Batchelor read some Scripture to them, and gave Alidy a Bible; he is a very good, sensible fellow, and will, I hope, be of great service to us at Nosi Mitsiou. Among the fruits we found to-day was one which grew in clusters, very like grapes, sweet in taste, but extremely glutinous; the natives use it in preparing the tamarind, name, tsimiranja; I saw some last year near Vatomandry.

August 11.--Got a good swim. Went to a lake distant about two miles, where we killed some tsiriry (wild duck). Saw many beautiful flowers and curious fruits. Got a bit of sandal wood, which they call here laza-laza. The fresh tamarind has a very pleasant acid taste. We had a visit to-day from a native of Suratra, Ismael Be, an English subject, and a very fine fellow. The funeral rites proceed. Every now and then we hear a strange noise like an animal in pain, and presently we become aware that a new arrival has commenced his wailing on his landing; this increases in vehemence till he arrives at the place where the body lies, and the people, who are assembled there, take it up. Then follow more beef, more rum, and more dancing to dispel this vehement grief. More talk this evening with Ismael Be; he is a very intelligent as well as a very handsome man.

August 12.--Got a swim before the sun was up, but there were many spectators. All the place astir early about the funeral. The procession of six boats started about 7; we watched them return, after which there was a grand kabary about our journey. One man was for making us pay, but he was snubbed, and told that if he did not take care he would be tied up. Then came the funeral feast. Batchelor sat by the king and talked to them. I went for a sketch, and found him still at it when I returned; he had been having some controversy with them. They told him that the Sultan of Turkey was the greatest monarch in the world, that God built Constantinople, and that 70 children, sons of the kings of the world, were sent to him annually to be educated. On being told that this was untrue, they replied that perhaps their children might know better, but that for themselves they were old, and must fare as best they might on what they had got; so we should have no difficulty about schools. A large number of the people are not Islamites, even by profession. What are they?--Just rationalistic heathens. The Mohammedans from this place send money to Mecca every year. Got off some of our luggage this evening.

August 13.--A swim by moonlight; romantic but cold. Got off in six canoes at 6.45. We gave Derimany a telescope and five dollars. It is hardly possible to conceive anything more picturesque than our departure. The old tamarind tree, the king and his people, and the six lakampiara. There was no wind, and we had to paddle. Passed by the towns of Antsahabe, Ralampenjika, Bobatsiratra, Rapan-dolo. Went ashore at this last town, had prayers with the servants, and a long talk with Alidy. Made up our minds to be off as soon as the moon was up, and accordingly rose at 2 a.m.; but owing to provoking delays, did not get off till nearly 4.

August 14.--Rounded Cape Sebastian at 5; beautiful sunrise. Saw the coast right up to Liverpool Sound (Antsakoa). Landed for breakfast on a beautiful sandy beach, where we found coral, shells, and sponge. Got on again to Befotaka Bay (loraka), and landed at a village called Fararano. (This bay runs up some distance, and the walk across the isthmus to Antufiambe cannot be above five miles.) We had to remain here the rest of the day; it is a low place, much given to toaka. Paid a visit to one of the huts, where I saw an old delft water-jug, which revived memories of old china days. Persuaded the lady of the house to sell us some wooden spoons. The towns of Befotaka and Tany Fotsy are on the opposite side of the bay. The summit of Mount Amber bears E.S.E. from this place.

August 15.--Did not get off till nearly 10; paddled some way, then up sail. We had now twelve canoes, and the scene was delightful; it was, in fact, quite a regatta. I took the measurement of one of these lakampiara, which was 26 feet long by 2 feet i inch broad in its widest part. They have no masts but two sprits, which are stepped into holes at the bottom of the boat. The breeze was light at first, but gradually freshened till we began to ship a good deal of water. At last, one of the sprits came to grief, which was a token to us that it was time to make for land, which we did. Putting into Loraka Talaka, went on a voyage of discovery, found some curious stones. There is a great quantity of mineral here. I saw traces of copper and the iron of course was abundant; but from the way in which reefs of quartz cropped up I am under the impression that the district is exceedingly rich. Waited for the breeze to abate, which it refused to do; so we had to lie down and get a few hours' rest in our tent. Alidy, who could not sleep himself, was very restless, and roused us up at 11.30; but we did not get off till 12.30, when we launched our canoes. There was still a stiff breeze and only starlight, but our men put out without any hesitation, and as soon as we had made an offing to fetch the point up went the sail. There was the same sort of "lop" on the water and we got very wet. It was very chilly and we quite enjoyed the waves coming in, they were so warm. At last we rounded the point and got into the bay, but the breeze was too strong for us, so we beached our canoes, and very soon fires were lighted, and we were drying our clothes and warming ourselves, for the breeze had been very fresh and we were quite cold. The scene around the fire was most wild and curious. The Antankara were in the wildest spirits, laughing and cracking their jokes, every now and then screaming and shouting; and the two Vazahas sitting composedly in the middle quite at home. As soon as we were warm and dry we lay down and got some sleep. We started again at 5, when the day was beginning to break; breeze still very stiff and right in our teeth. There was no deception whatever in the two hours' work that the men had. The bay was very shallow and they got out, and they eased themselves occasionally by hauling the canoes along, and sometimes by punting them. Landed at Andramaimbo at 7 A.M., where we were met and courteously received by a Banian Indian who was there with his dhow, and who is building a house, but in the meanwhile has a small store in a leaf hut. He was a large man, of very peculiar figure; a bargaining between him and Alidy was most amusing, it was "diamond cut diamond," but the Indian had the best of it. Got a sketch. We are to remain here all day. In the afternoon Batchelor and I started for a walk, we followed the track to Antomboka and got to the top of the central ridge in half-an-hour. There was a fine ridge, very sharp and steep, running north which we determined to climb. It was so narrow that I could sit astride on it, and all but precipitous. The views were very fine as we ascended, and we could see the Mozambique on the west, and the Indian Ocean, and Diegosoarez bay in British Sound on the east. I found all the old zest for climbing fall upon me. We passed up through a charming bit of forest, and in the midst of it came upon a very beautiful silver-grey lemur, who looked at us with its bright large eyes and then sped away. When we emerged from the forest we had still some way to go to reach the highest point from which we could see all round Cape Amber. It was now very near sundown, so we took our bearings and commenced our descent, making straight for our tent. Our first essay was a mistake, we came upon an impracticable (at that hour) rock, so we harked back, losing thereby an exceedingly valuable half-hour. The slope down which we went was covered with long grass, in which were hidden innumerable stones and rocks, which made our progress hazardous and slow. We constantly came upon the lairs and tracks of wild boars, but saw none. As we passed one wood I gave a shout, which was answered by the lemurs, which, came to the edge of their forest to see us, but it was too dark now to make them out. We made our point all right, but when we got to the shore we could not hit upon our tent. We had in fact worked too far north. I led south at first, but we got into so much mud, the end of which was uncertain, that we had to retrace our steps. It was now quite dark, and I fancied that we had got too far south, but Batchelor had his bearings and took the lead. I was quite done, and felt disposed to light a fire and make a night of it, but the recollection of our men kept us going, and at last we hit the sea-shore again and found ourselves in the right track, but the last two miles were exceedingly trying. Once we came suddenly on a deep ditch round which we could find no path, and right glad we were to reach our tent. The men came in. Alidy with his sword of office, and made a regular kabary about our return, for they said that if we had been lost or any harm had happened to us, they would inevitably have lost their lives, if not at the hands of the Hovah, certainly at the hands of their own people; of such consequence are the Vazaha. To bed very tired.

Aug. 16.--Got off at 5.40. Walked on briskly till 8; then I began to want shade and water. Stopped a little and enjoyed some cold tea and biscuit. Then on again till we got to the edge of a bit of forest, which we entered, and presently heard voices. All at once we came upon a most enchanting scene, a fine sparkling stream--the Antomboka--flowing between finely-wooded banks. The trees wide apart, and very little under-growth; it was most delicious. The men washed themselves and their clothes; Batchelor bathed; I was too lazy. After an hour's rest we went on to a particularly miserable town, called Namakia, where we got some food in a very dirty house; after this we had to walk three quarters of a mile to another part of the village, where we found a larger, if not a cleaner house, but the people were most unwilling to leave it. I swung my hammock and reposed, while Batchelor kept up a kabary with Alidy and Tsindriana; presently we heard the drum (langaroon) and music, and we were told that the commander had sent for us. Accordingly four soldiers presently arrived with a manan honinahitra (man of honour), and we were escorted with military honours to the Rova, where the Governor in full fig was awaiting our arrival; here ensued a scene which baffles all description. The kabary of the Antankara introducing us, and of the Hovah commander receiving us, no pen can possibly describe. The former asserted boldly that next to Queen Victoria we were the greatest men of the English nation; that King Ratsimiaro had shown us all his possessions, and given us one of every description of live stock which he possessed. Then the Governor Taratahy replied in suitable terms, and conducted us into his house where toaka was handed round, and we drank every one's health, including our own. He showed us his baby, a very jolly child, who let me take him up. Then came the crowning act--the commander to show that he was ravoravo indrindra, i.e. perfectly enchanted at our coming, got up and danced a pas seul, we of course looking gravely on, and nodding our heads in time. At last we got away, the commander escorting us after we had gone through the usual Hovah dress parade, and presented us with a bullock and much rice.